This is a short piece that I wrote about Frances Wisner, the last of the mountain women, not long after I learned of her death in January, 1986. She lived 72 years, most of it—45 years to be exact—along the Salmon River, deep within the Central Idaho Wilderness. She buried two husbands, and for the last 20 years of her life she lived alone tending her garden and writing a column for the Grangeville newspaper..

We stand outside the fence, looking longingly at the cabin and watching the soft luminance from a window spill out over the snow. It is dark. We are soaked to the bone and chilled. We know it will be warm and dry inside, but we are hesitant to announce our presence—or, for that matter, to make any noise.

It has been a miserable day. Most of the day it had rained, and the snow pack was so soaked that with almost every other step, our skis broke through, plunging through several feet of snow nearly to the ground. It hadn't been the most dignified demonstration of downhill ski technique. Time and time again, we'd lose control, and fall with heavy packs hurtling us face forward into the mush. Moreover, it certainly wasn't what we had expected. It was downhill, after all, over 4,000 feet of downhill, all the way down to the Salmon River and Frances's place.

Here we stand, finally at Frances's cabin, deep in the central Idaho wilderness, dozens of miles from the nearest plowed road, cold, tired, haggard, and all we can do is to stare at a cow bell dangling from a wire on the gate. The cowbell, by the way, is Frances's door bell, but no one is willing to shake it.

You see, this is Frances Wisner that we're talking about—and Frances is no ordinary woman. She is, in fact, known in these parts as the last of the mountain women, the last remaining member of an extraordinary group of self-reliant women who by physical and mental prowess, lived and forged their place in the western wilderness. For years and years, she has lived here, many of them all alone. Living here has taught her well. She can take care of herself which in this country means that she knows how to use a gun. And she is deadly with it. And she doesn't like surprises.

You see, this is Frances Wisner that we're talking about—and Frances is no ordinary woman. She is, in fact, known in these parts as the last of the mountain women, the last remaining member of an extraordinary group of self-reliant women who by physical and mental prowess, lived and forged their place in the western wilderness. For years and years, she has lived here, many of them all alone. Living here has taught her well. She can take care of herself which in this country means that she knows how to use a gun. And she is deadly with it. And she doesn't like surprises.

All that is going through our heads as we stand looking at the cow bell. Finally, the promise of warmth inside is too much, and I reached out tentatively. Then shake the bell.

We hear a muffled metallic sound inside. The sharp click of a latch. The door of the cabin bursts open. A flash of light streaks out across the snow. The sudden bright light blinds us. At any sign of a rifle barrel we are ready to spring out of the way.

"Who's out there," demands a rough feminine voice from the doorway.

"It's the skiers." I quickly reply. I try to follow it up with something reassuring but I'm completely unable to think of anything else.

"The skiers?" the voice asks.

There's a long pause, and then, she says "Well, come on in here!"

* * *

It has taken us two weeks to get here. It is late February. We are on a ski traverse—a sort of a backpacking trip on skis—which will eventually take us some 200 miles across the central Idaho wilderness. There are four us: Scott Finholt, Sandy Gebhards, Pete Casavina and myself. We're about half way through the trip and we are relieved that Frances has invited us in.

We file into her kitchen, a small cramped room with jars, pots and utensils piled on counter tops. The room seems smaller yet by a monstrosity of a cast iron cooking stove which sits against an outside wall. On the wall near the door a sign reads, "This kitchen belongs to Frances. If you don’t think so just start something." Another reads: "This is my house and I’ll do as I damn well please."

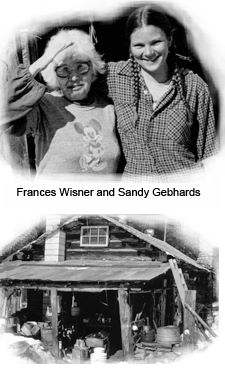

Frances, a diminutive woman with white, wind-ruffled hair, sits down and props her legs up on the stove. She wears green checked polyester pants and gray T-shirt with a caricature of Mickey Mouse on the front.

Frances, a diminutive woman with white, wind-ruffled hair, sits down and props her legs up on the stove. She wears green checked polyester pants and gray T-shirt with a caricature of Mickey Mouse on the front.

We crowd near the stove. Its warmth begins to sink in and steam rises from our wet clothing. She stops abruptly from telling us about the stove, and locks a cold stare on me. "You, a member of the Sierra Club?" she asks in a voice that settles so heavily that I nearly have to catch my breath before I answered.

"No," I say. (I wasn’t at the time). Then she turns, with the same cold eyes, staring one by one at each of the other members of our group, asking the same question. They all answer "No."

She eases back and says "Good. Then I don’t have to throw you out!"

I have absolutely no doubt that Frances would have sent us scurrying out of her warm, inviting cabin had one of us been a member. Instead we sit, packed in the small, and increasing steamy kitchen, with Frances feeding us beans and pan-fried corn bread.

Life is abundant with hidden irony—and it always seems that irony is never more hidden from us than when it deals with things close and dear to our hearts. Although Frances had no love for the Sierra Club, it was partially through the Club's efforts that her lifestyle and the beautiful country which she so loved were eventually protected. Had not central Idaho received formal congressional protection as the River of No Return Wilderness area, there's little doubt that much of the Chamberlain Basin, the country above her cabin would be roaded and logged by now.

It was true that I wasn't a member of the Sierra Club, but I did serve on the board of directors of the River of No Return Wilderness Council, the Idaho group which worked for years to preserve the wild, untracked heartland of the state where she lived. If Frances had asked me about my other environmental associations, she would have booted me out, and I would have spent the night sleeping in a snow bank. Fortunately, the conversation moved on, and I prudently avoided volunteering any other information on the subject.

* * *

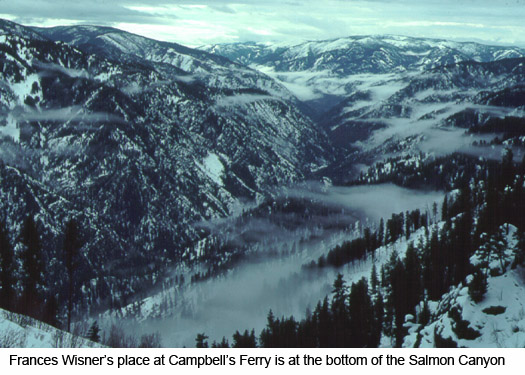

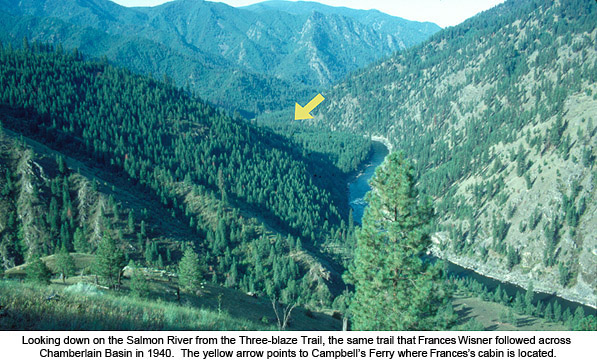

Frances came to Idaho in 1940, riding a horse across Chamberlain Basin, the high lodgepole forested country lying south of the stretch of the Salmon known as the River of No Return. She rode north, following the three-blaze trail and descended into the Salmon River Canyon. The trail crossed the river at a place called Campbell’s Ferry. Seeing Campbell’s Ferry for the first time, she described it as "the most beautiful place in the world." To her, it was the promised land—and there in her promised land she settled.  Down the river, nine miles from Frances’ place, lived perhaps the most well known figure in the Idaho Wilderness. His name was Sylvan Hart, or more famously, Buckskin Bill. By the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, Buckskin was widely known through a best selling book written by Harold Peterson entitled The Last of the Mountain Men. The publicity didn't stop there. Others came to visit, and he was the subject of numerous articles and even television appearances.

Down the river, nine miles from Frances’ place, lived perhaps the most well known figure in the Idaho Wilderness. His name was Sylvan Hart, or more famously, Buckskin Bill. By the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, Buckskin was widely known through a best selling book written by Harold Peterson entitled The Last of the Mountain Men. The publicity didn't stop there. Others came to visit, and he was the subject of numerous articles and even television appearances.

But part of the Buckskin image was pure hype. He didn’t live miles away from the nearest road as many believed. A jeep trail ended practically across the river from his place. A short 3½ miles distance down river was Mackay Bar, a fly-in dude ranch. The first time I ever saw the legendary character, he was out on the sandy beach in front of his place repairing an all-terrain vehicle. And next door to Buckskin’s place was incongruous yellow prefabricated house built by one of his relatives.

But part of the Buckskin image was pure hype. He didn’t live miles away from the nearest road as many believed. A jeep trail ended practically across the river from his place. A short 3½ miles distance down river was Mackay Bar, a fly-in dude ranch. The first time I ever saw the legendary character, he was out on the sandy beach in front of his place repairing an all-terrain vehicle. And next door to Buckskin’s place was incongruous yellow prefabricated house built by one of his relatives.

Frances said that Buckskin, himself, wasn’t happy about some of the hype. According to Frances, Buckskin had called Peterson's book "a crock of crap." As an example, she cited a problem with the book: "Buckskin like tea?" She asked. Then, pausing for effect, she answered. "Don’t ever offer Buckskin a cup of tea!"

In many ways Frances and Buckskin were similar. Both were independent, proud and iconoclastic. Mostly, they wanted little to do with the outside world. On the other hand, in other ways they differed. Frances was actually further removed from civilization than Buckskin, having no jeep trail across the river and no prefabricated houses built next door. If Buckskin deserved his title, then she most imminently deserved to be called the Last of the Mountain Women.

There was one thing in which they both agreed: they both detested the Sierra Club. They feared that wilderness designation sought by the club for the Salmon country would take away their homes. It was, in fact, an understandable fear, particularly in the case of Frances. One year, some foolish and tactless member of a Sierra Club float group told her that she would have to move from her home when the area became a wilderness.

It was blustering malarkey. No reasonable conservationist or conservation group had ever advocated anything like that. The River of No Return Council, the primary organization working for the protection of the area, clearly supported protecting the homes of long-time backcountry residents like Frances, and consequently, when the River of No Return Wilderness bill was signed into law it allowed for private in-holdings. In the end, Frances was able to live out the rest of her life in her cabin listening to the peaceful flow of the river and not that of bulldozers echoing from the high country above.

***

Frances was never the religious type. Instead she lived a life of simple rights and wrongs, generosity to friends and straight talk to all. Frances swore that she’d never allow a member of the Sierra Club to set foot in her home, "unless," she said, "one is injured. I’ll help ‘em. But just enough to get him on his feet and out of here."

She was fond of telling her visitors that she hadn’t quite read all the piles of books scattered throughout her cabin. She avoided, she said with her wry sense of humor, the books sent to her by those intent on saving her soul. Despite her avoidance of organized religion, Frances did struggle with one devil in her later years. It was the devil of cancer which later claimed her life.

But cancer is a long way from her thoughts. Right now Frances is thoroughly enjoying herself, her eyes warm and alive, as she tells her stories before a rapt audience. Fortunately, she doesn't seem to mind the half-clothed condition—or smell—of her audience. With the cook stove on full blast, we're mostly down to our ripe, long underwear and steaming clothing are everywhere, hanging from nails and hooks.

Company is something that's a rare commodity in the winter for Frances, most particularly the company of women, and you can tell she is delighted with Sandy's presence. I suspect she sees something of herself in Sandy. And Sandy perhaps sees something of herself in Frances.

Sandy has been an invaluable member of the party. A rugby player, she is strong and carries a veritable sporting goods store with her. Whenever, we need something, Sandy has it—from extra seasonings to spice up our freeze dried meals, to a snow saw for building igloos, to binding parts, and tools to repair nearly anything that's broken. Sandy is also pretty smart. She is happy to loan out things from her pack as long as the borrower understands that he now is entrusted to carry them. In this manner, her pack has lightened over the last couple of weeks. It strikes me that Frances might have made the same sort of arrangement had she'd been a bit younger and along with us on the journey.

Sandy has been an invaluable member of the party. A rugby player, she is strong and carries a veritable sporting goods store with her. Whenever, we need something, Sandy has it—from extra seasonings to spice up our freeze dried meals, to a snow saw for building igloos, to binding parts, and tools to repair nearly anything that's broken. Sandy is also pretty smart. She is happy to loan out things from her pack as long as the borrower understands that he now is entrusted to carry them. In this manner, her pack has lightened over the last couple of weeks. It strikes me that Frances might have made the same sort of arrangement had she'd been a bit younger and along with us on the journey.

We are something of a novelty to Frances, though not much surprises her. She's seen a lot of people come and go. But few come in the winter—and, in recent years, no one has ever come by her cabin on skis. If you were to look further back in time, however, skis were once a very common way of getting around in the backcountry of the Intermountain West. Skis were particularly well suited to travel through snowbound central Idaho since the trees are sparse. Prior to Frances's arrival, during the gold rush days of the late 1800's and early 1900's miners used to skis to travel the backcountry when the snow was too deep for horses and mules.

On a Salmon River tributary downstream from Frances's place lies the site of the old mining town of Florence. During the winter of 1861-62 one of the most amazing migrations in ski history took place. It was one of the worst winters on record, and during the height of it, dozens of miners, using what we now call cross-country skis, traveled through the high, and deeply drifted Camas Prairie to reach the new and fabulous gold discoveries at Florence. A few decades later, around the turn of the century, there was another spurt of skiing associated with Thunder Mountain gold rush. Miners coming from north Idaho and traveling to Thunder Mountain would cross the Salmon River at Campbell's Ferry, a place which later became Frances's home.

***

After spending the night at Frances's place, our party split. Sandy, Peter and Scott decided to call it quits. Storms earlier in the journey had put us way behind schedule, and they had to get back to jobs and school. They skied to a ranch with a landing strip upriver from Frances's place and flew out a couple of days later with the mail plane. I had a few more days of vacation time and decided to continue the trip. I was lucky. Over the next couple of weeks, things went well. The temperature cooled off, solidifying the snow pack and I was able to ski up and out of the canyon and the remaining distance across the River of No Return Wilderness. But that's another story, and this story about Frances isn't quite finished.

I saw Frances a couple of other times after that winter, stopping now and then while on summer float trips down the Salmon River. The last time I saw her before she passed away, we sat on a bench in front of her cabin in the shade of a black walnut tree. A small diverted stream flowing near our feet served as both her domestic water and dish washer. As we talked, a few dishes rattled together in the cool, flowing stream.

Nearby fires were blackening the canyon down river and she was concerned about the tinder dry forests and fields surrounding her cabin. Concern ran so high that the shoes of horses grazing in her pasture had been removed. Responding to my questioning look, she leaned over and fastened those cold eyes on me. "Ever seen horse shoes at night?" she asked. "They make sparks!"

Then, she looked up and around at the surrounding countryside and her eyes softened. That's just the way I remember her eyes when four tired and wet skiers sat around her stove listening to her stories and eating beans and pan-fried corn bread. And, I bet that's the way they looked when she was seeing it all for the first time: Campbell's Ferry, her promised land and home.

END

A Great Read...

If you enjoyed these stories, you would also enjoy Never Turn Back. It's been widely acclaimed by reviewers and readers alike. The standard book trade reference Books in Print calls it a "masterfully written book" and "one the outdoor world's finest works." The book also appears on a number of best reading lists. Click here for more information. |

||||

And Another . . .

The book is truly a classic, one reviewer calling it the "standard by which other guidebooks are judged." Click here for more information on Winter Tales and Trails.

|

||||

More Resources...Frances Wisner's cabin and ranch at Campbell's Ferry has been preserved thanks to a series of dedicated individuals. For more information on Campbell's Ferry and the preservation efforts, see Campbell's Ferry: Historic Idaho Homestead.

The story about Frances Wisner takes place along Idaho's River of No Return (Salmon River). One of the best books on the colorful history of the old-timers that lived along the river is Cort Conley's River of No Return. More Information.

The story of Buckskin Bill who lived downriver from Frances is found in The Last of the Mountain Men: The True Story of an Idaho Solitary. More Information.

A collection of Frances Wisner's writings can be found in My Mountains: Where the River Still Runs Downhill. The book is out of print and very, very difficult to find. The surest bet to find a copy is to visit an Idaho library. You'll have better luck with with Carol Furey-Werhan's book: Haven in the wilderness: The story of Frances Zaunmiller Wisner of Campbell's Ferry, Idaho The book is out of print as well, but it is available from used book dealers: More Information.

A beautifully illustrated book is now available of the River of No Return country. Entitled Salmon River Country, the book is by award-winning photographer Mark Lisk and writer Stephen Stuebner. It's a colorful view of Salmon River Country and some of the hardy people who live and work along the river. More Information

|

||||

If you are interested in more stories of skiing in the old days, you'll want to pick up a copy of Winter Tales and Trails. It's full of historic information on skiing. Plus, it's a guidebook to backcountry, cross-country and snowshoeing trails in Idaho, Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks.

If you are interested in more stories of skiing in the old days, you'll want to pick up a copy of Winter Tales and Trails. It's full of historic information on skiing. Plus, it's a guidebook to backcountry, cross-country and snowshoeing trails in Idaho, Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks.