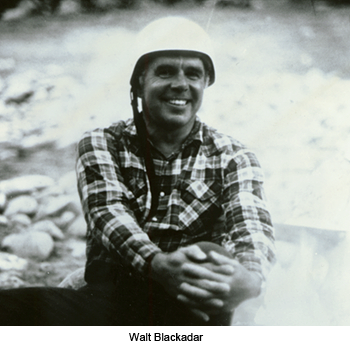

This true tale is a different sort of sea faring story. It's not about wooden sailing ships or fishing boats weathering big storms. Rather it's about a group of river rafters with no ocean-going experience who make a risky, all-night journey across the capricious seas of the Gulf of Alaska. It's also very much the story of a man, Walt Blackadar, who in his mid 50s is desperately trying to hold onto something nearly gone. The story appears in one of the chapters of Never Turn Back.

When it was first told to me by one of the participants, I found it a haunting story. Retelling one part of it, the anecdote of a small boat motoring across the Gulf, would have been interesting enough, but when it is combined with Blackadar's story, it takes on a surreal and frightening quality. .

South and west of the Gulf of Alaska lies the great curving dome of the Pacific Ocean. For thousands of miles, there is nothing but salt water. Even traveling at speeds of hundreds of miles per hour, jet passengers sit for monotonous hours flying over the expansive ocean on the flight between Anchorage and Tokyo. Where the Alsek River enters the Gulf of Alaska at Dry Bay, there are no protecting islands to block the weather which rolls across the northern seas, and, in fact, the mainland coast of southeast Alaska is exposed to the full force of the Pacific storms except in the south where it is protected by the series of large islands making up the Alexander Archipelago.

The hundred miles of open ocean extending south between Dry Bay and Cape Spencer, which marks the beginning of the protected waters of the Alexander Archipelago, is not a place to be in a small raft. Throughout a good part of the stretch, the seas break into a broken, rocky shore, and there are few safe places to land. It was, nonetheless, across this hundred mile stretch that Walt Blackadar wanted to try to take rafts.

Blackadar, the whitewater world's most famous personality, had no seafaring experience in his background, but the idea of floating down a river and boating back to civilization by way of the ocean appealed to him. His idea was to run the Tatshenshini River which flows into the lower Alsek. At Dry Bay, Blackadar planned to have Layton Bennett fly in two outboard motors which would be used to propel the rafts, following a course close to the shoreline, around Cape Spencer into Cross Sound, past the spectacular Glacier Bay area, through Icy Strait, and on to Juneau, a distance of 175 miles. It was a circular journey, starting in Juneau with a ferry ride, and ending in Juneau, with the St. Elias wilderness and the great glaciated coastline of southeast Alaska in between, traveling on land, river and sea. It was ambitious, adventurous, aesthetic, and dangerous. Just the perfect combination.

From the appearance of his early correspondence, Blackadar did not understand the full nature of the undertaking. In March of the year, he had written to Doug Wheat, a teacher and avid kayaker from Colorado, telling of his plans: “We are now contemplating using the raft on the open ocean and touring back by way of Glacier Bay National Monument . . . . There is probably sixty miles of open, unprotected ocean that would have to be boated. But the shoreline is kind and there is sand beach most of the way and if a storm comes up, I feel we would have no problem in beaching the rafts and kayaks and going ashore.” As Blackadar would find out on the trip, however, there were few safe sandy beaches and practically no place to take refuge on shore.

Wheat was planning his own trip on the Tatshenshini, and Blackadar suggested that they combine groups. Having the same trouble as he did for the Susitna trip, Blackadar had only interested one other person in his trip, and combining with Wheat bolstered the size of the group. When Blackadar arrived in Juneau, he joined a party consisting largely of Colorado boaters put together by Wheat: Gary Young and John Wilhelm, who were both involved in a river guiding business out of Colorado; Tom Johnson, who kept a detailed diary of the trip; and Dieter Weck, who was the only other member of the party close to Blackadar’s age. Weck, a German baker living in Colorado Springs, was planning to prepare donuts, cake, pizza, and other delectable pastries, not a simple task on the wet banks of an Alaskan river. Several others from Colorado joined the trip, bringing the total to 10.

The group took the Alaska Ferry to Haines and hired a driver to take them to the start of the Tatshenshini off the Alaskan Highway. Since the put-in is on Canadian soil, they stopped at a customs entry port on the Haines Road. The customs official, looking over the group which appeared particularly ragged in their outdoor wear, called for a thorough search. Packs were emptied and sleeping bags unrolled.

“Walt was indignant,” said Wheat. “He was telling him [the customs official] off.” Everyone was tense during the search, and Blackadar certainly had reason to be concerned. After nothing was found and the official let the group continue, Blackadar reached into his gear and pulled out a book with a false center. Inside was his pistol and a bag of marijuana. “If you guys need anything,” he told his stunned companions staring at the book, “I’ve got it.”

It wasn’t Blackadar’s only disregard for Canadian authority. He had also brought along a gill net, which he would use to catch salmon for dinner while on the river. The procedure was and is illegal, but Blackadar was a curious mix: an ardent environmentalist with disdain for authority. At one point on the trip, a helicopter flew low overhead as the gill net was in place. The helicopter was thought by the party to be returning to pick up some Fish and Game officers they had passed earlier. Again, the group was tense and “unnerved,” for the distinctive floats of the net could easily be spotted by an observant game officer. The helicopter moved in closer and started to settle down for a landing.

It wasn’t Blackadar’s only disregard for Canadian authority. He had also brought along a gill net, which he would use to catch salmon for dinner while on the river. The procedure was and is illegal, but Blackadar was a curious mix: an ardent environmentalist with disdain for authority. At one point on the trip, a helicopter flew low overhead as the gill net was in place. The helicopter was thought by the party to be returning to pick up some Fish and Game officers they had passed earlier. Again, the group was tense and “unnerved,” for the distinctive floats of the net could easily be spotted by an observant game officer. The helicopter moved in closer and started to settle down for a landing.

“I had no affection for going to jail,” wrote Tom Johnson, describing the experience. After hovering for about a half minute, the copter inexplicably took off, and, to everyone’s relief, disappeared. The net was removed from the water and hidden in the bottom of a waterproof bag. But the next morning the net had again found its way back out in the water, and an eight-to-nine pound silver salmon was caught, filleted and broiled for breakfast. Salmon continued to supplement their meals throughout the trip.

Blackadar told the others that if the helicopter had landed he would have gone out with them. He was terribly sore, he said. His shoulder ached, his hands hurt, with the deep cuts of rope marks still showing from trying to hold the line attached to his boat in the Nozzle eddy. To top it off, early on the Tatshenshini trip, he had banged his knee trying to free a boat caught on some rocks, and it was now sore and swollen.

Despite his physical ailments, he rowed the raft and traded off in the kayaks as they made their way down the river. At night while Dieter prepared pastries, Blackadar entertained the group with stories of his most recent Susitna trip. “It was the Susitna that really obsessed him,” said Gary Young. “It consumed the conversation the whole time [early on the trip]. He wanted to go back and try it again. It was one river that was not going to beat him.”

Blackadar also bragged about his prowess with a pistol. Rising one night early on the trip, he seized his .44 and told the others he would prove his skill to them. “Reeling around, he tells us to throw beer cans up in the air,” said Wheat, “which we did obediently, cautioning him to please go easy. Here he is—the perfect Lee Marvin, Cat Ballou-type drunk—weaving and bobbing. Everyone [else in the group] is hiding and crouching down. And he hit every one of those beer cans. He hit them in midair . . . .”

As the party neared Dry Bay, the current eased into the large lake that has formed below Alsek Glacier. While they drifted around the lake and marveled at the silent, blue icebergs released by the glacier and floating like giant chips of broken china, they collected pieces of ice to replenish their coolers. On the way out of the lake, Blackadar climbed from the raft onto one of the small icebergs and stood on top of it, riding down the river for several miles. “I’m having a blast,” he yelled to the others before he was picked up. The real blast was yet to come.

* * *

By coincidence, Klaus Streckman, a good firend of Blackadar's was also on the Tatshenshini that week. He came upon Blackadar and his group on the lower river. When hearing of Blackadar’s plans to motor out across the ocean, Klaus was enthused and asked to join them. Blackadar democratically cleared it with the others, assuring them that Streckman was good in emergencies and a strong addition to their party. Already, some members of the group were realizing that traveling across the open ocean would not be a picnic, so Klaus was welcomed in.

By coincidence, Klaus Streckman, a good firend of Blackadar's was also on the Tatshenshini that week. He came upon Blackadar and his group on the lower river. When hearing of Blackadar’s plans to motor out across the ocean, Klaus was enthused and asked to join them. Blackadar democratically cleared it with the others, assuring them that Streckman was good in emergencies and a strong addition to their party. Already, some members of the group were realizing that traveling across the open ocean would not be a picnic, so Klaus was welcomed in.

The fishermen working at the small Dry Bay fish camp scoffed at the plan, warning that the trip was foolish. One of the major problems, the fishermen told them, was the winds which come from the southeast, sometimes appearing as frequently as three times a week. A raft with a small outboard trying to make its way south could not travel against such winds and would be blown in the opposite direction. Doug Wheat said later that at the time he “was very apprehensive about the ocean and I voted against it.” On the other hand, the majority wanted to try it, and from the fish camp, Blackadar radioed Layton Bennett to fly in some extra supplies and the two 20-horse Mercury motors which had been left at the airport.

When the plane arrived, Gary Young remembers being perturbed when they started pulling out the supplies which consisted of “mostly booze and Wyler’s lemonade and very little food. That was about the only time we got pissed at him,” Young said. They were counting on having plenty of rations for the trip.

Blackadar continued to tell the group not to worry, and if they had any problems, they’d just go to the shore and beach the boats. Blackadar had even brought a crab pot along, which would help supplement meals. The two rafts were lashed together and the motors mounted in place. With a favorable weather forecast—winds from the west—the eight people climbed on board the two 16-foot-long rafts, crowding in among cans of gas, food, beer, waterproof bags, camping gear, Blackadar’s crab pot, and three kayaks.

They carefully motored out of the bay through fog, rising up and over large rolling waves, and then, happily, upon leaving the bay, they broke out of the fog into sunlight and calm seas. The sun illuminated the snow and ice-covered peaks of the Fairweather Range as they traveled south. It was a beautiful southeastern Alaska panorama, but several members of the party weren’t able to enjoy the view, having become seasick in the swaying boats. The ocean never seemed to bother Blackadar, though. “I was jealous of Walt, watching him put down beers,” wrote Tom Johnson, who was one of those who felt ill, “when I could not even drink one . . . all the while Walt is yelling that he was having a great time.”

They made good time with a breeze pushing them south. As evening came on, a decision was made to continue through the night. The weather looked favorable, the seas were right, and according to Wheat, in reality, they had no other choice. “We could not go to shore,” he said. “Imagine rocks from car size up to house size on the shoreline. There was no beach at all. Walt said there’d be a beach. He said, ‘Ya, we’ll just pull in and do some beachcombing. We’ll probably find those glass balls from China and all kinds of treasures along the beach.’ Well, that was completely out of the question. We were completely committed to the ocean.”

Darkness settled on the coast. Blackadar lined up the boat with the stars, and Wheat and Streckman used the compass. Overhead, the northern lights flamed elusively and outlined the Fairweather Range. The waters under them glowed with a fluorescent plankton, particularly showy in Alaskan waters.

With nightfall, the temperature dropped, and the wind came up. Chilled, the raft riders crouched down between gear bags, seeking places out of the wind. As the waves picked up, Klaus Streckman watched anxiously for any signs of breakers. He had some ocean experience and, perhaps more than the others, knew how vulnerable they were. As the night went on, the sea built. The rafts undulated nauseously, providing little relief to those who were sick, and on occasion, one would hang his head over the edge, throwing up.

Approaching Lituya Bay, which was approximately 50 miles south of Dry Bay, the swells were reaching 15 to 20 feet in height. Lituya Bay’s narrow 1,000-foot entrance at low tide is known for its hazardous tidal currents. In 1786, when the bay was first discovered by French explorer La Perouse, 21 men drowned when three small boats surveying the entrance were swept into a tidal bore.

The tidal currents at the entrance of the bay bothered them, so unsure of their position in the dark night they decided that they would pass it. At approximately 1:30 in the morning, just before the opening of the bay, they had their closest call.

The tidal currents at the entrance of the bay bothered them, so unsure of their position in the dark night they decided that they would pass it. At approximately 1:30 in the morning, just before the opening of the bay, they had their closest call.

Klaus, still wide awake and keeping up his vigil, looked through the darkness for any signs of breakers or rocks. Then he saw it. Outlined in the glowing fluorescent plankton, he could see the breaking sea plainly, pounding against rocks. “We were perhaps two swells away from crashing,” said Streckman. “It was a major emergency.”

Streckman yelled to Wheat, who was running one of the motors, to turn away. Blackadar, waking, wondered what the excitement was about. Streckman and Wheat quickly explained, but Blackadar told them to relax and to remain on the same course. It seemed to Wheat that Blackadar had no concept of the danger. Ignoring the doctor, Wheat pointed to the right, and the rafts swung around. Since the boats were now exposed sideways to the waves, water splashed over gunwales, wetting the already cold occupants. Blackadar grumbled and wanted to return to prior course, but with more of the party realizing their danger, he was outvoted. “We were concerned enough with the situation that we didn’t pay a whole lot of attention to Walt,” said Wheat. “We were trying to save our skins.”

Sideways in the waves, the two boats started separating. Streckman leaped to the front of the boats, trying to hold them together. Waves crashed over the top of him, and afraid that he might wash away, somebody in the dark nearby held his feet. Streckman had been doing fairly well up to this point, but bouncing up and down on the bow, trying to relash the boats together was too much, and he got seasick.

Once the boats were secured, the nauseated Streckman returned to his watch. Blackadar fell asleep, woke once, looked around and said, “I’m having a blast,” and then drifted off to sleep. Another time he woke up to a conversation in which the others were concerned about their position. “No problem,” he said. “I’ve got Gary’s head lined up with the moon. We’re right on course.”

As they motored along, with the rafts bucking in the waves, the shadowy outline showing off the Fairweather Mountains to their left, and the stars and northern lights overhead, Blackadar, with his eyes wide open, looked over at Wheat. “Doug,” he said solemnly. “This is a night that you will never forget.”

“He was right,” said Wheat years later. “None us will ever forget.” Finally around noon the next day, after the long, unforgettable night, the tired group reached the safety of Dixon Harbor, just north of Cape Spencer. They dragged the boats up on the beach, dropped their wet things, scrounged a quick meal, and scattered about, most falling quickly to sleep.

END

A Great Read...

.If you enjoyed this story, you would enjoy the book from which it was taken. The title of the book is Never Turn Back. It's been widely acclaimed by reviewers and readers alike. The standard book trade reference Books in Print calls it a " masterfully written book" and "one the outdoor world's finest works." The book also appears on a number of best reading lists. Click here for more information. |

Other References:

La Pérouse: More information on La Pérouse can be found in The Explorers: From the Ancient World to the Present by Paolo Novaresio. This is a beautifully illustrated book with a wealth of information on exploration. More Information.

Glacier Bay National Park: Another beautifully illustrated book is Mark Kelly's Glacier Bay. More Information.

Inside Passage: Art Wolfe, a superb nature photographer, has a lavish book on the Inside Passage (The Inside Passage to Alaska). More Information. |