Copyright & Revisions: Revised, reformatted and updated in 2012. Original copyright © 1996. Reproduction information: you are welcome to provide links to this page or to use short quotations and paraphrases in other documents as long as they appropriately reference the source. If you plan to reproduce or publish extensive parts or all of this paper, please obtain advanced permission from Ron Watters (wattron@isu.edu).

Publication History: Published in the Journal of Physical Education, Receation and Dance, May/June, 1996, Volume 67, Number 5, pp. 55-56.

Editor's Note: This is the shorten version of a longer article entitled The Art of Teaching Map and Compass: Instructional Techniques, Curricular Formats and Practical Field Exercises which was published in the Proceedings of the 1996 International Conference on Outdoor Recreation on Education.

Abstract

The value of teaching map and compass in a classroom or an outdoor situation is often overlooked. A common impression held by many is that it is dry and unappealing. But, in reality, when taught correctly using a combination of exercises indoors and outdoors, map and compass can be one of the most enjoyable of all outdoor activities, generating excitement and enthusiasm even among the most reserved students. Moreover, the importance of navigation knowledge can't be overlooked. It is the most basic of all outdoor skills and has applications which carry over to every day life. A map and compass curriculum is easy to incorporate into any school or outdoor programming situation, requiring a minimum of equipment. This paper discusses general teaching principles, including some ideas on how to deal with one of the most vexing problem areas for teachers: declination. One teaching scenarios is suggested. The paper concludes with an annotated list of map and compass references.

Introduction Map and compass is one of those areas of outdoor education that we tend to overlook. At first glance, it isn't as sexy as rock climbing or as in vogue as rope course or team building activities. It seems, well, to put it mildly, that map work is rather dry stuff. It's this unappealing image of map and compass which makes it something easily forgotten or glossed over. At second glance, however, there is much more to the subject than meets the eye. First and foremost, map and compass is the most basic of all outdoor skills. No matter what a person does in the outdoors--hike, cross-country ski, hunt, canoe, or sail--he or she will need to know something about maps and compasses. Moreover, the knowledge of rudimentary wayfinding techniques is important and useful in day to day living.

One of the nicest things about teaching map and compass is that it is truly the great equalizer, whether it is taught in a classroom or in an outdoor setting. It plays no favorites. It's for everyone: children or adults, men or women. It is a type of activity which transcends gender and ethnic boundaries. It can even be taught in the early grades when children first start going to school. The idea that only older children should be exposed to map and compass instruction is passe. Recent research (Blades & Spencer, 1989) indicates that very young children can learn and benefit from basic wayfinding skills. With its low cost, high value and ease to incorporate in a variety of educational situations, map and compass should be a part of any outdoor activity program. The following are some teaching suggestions, hints and curriculum ideas. It assumes that you are already familiar with map basics, but if you need to brush up on navigation concepts, a list of source materials has been included at the end of this paper.

What is Needed The equipment needed for teaching map and compass is relatively inexpensive. For younger children, a simple map of the school yard (costing nothing) is all that is necessary. Older children and adults will need topographic maps ($8 dollars each), but since topographic maps are made by the U.S. Geological Survey, an agency of the federal government, they are in the public domain and may be photocopied as many times as needed without worrying about copyright infringement. The most expensive part of teaching map and compass instruction is compasses. Compasses, however, aren't needed for young children. For all others, the expense is low. The finest compasses for outdoor use only cost around $50. The compass I use in my classes is the classic Silva Ranger. You can set the declination on the the Silva which is a huge advantage when teaching. If that's a bit out of your price range, adequate compasses can be found for around $15. While you can't set the declination, the Silva Polaris (with a slight modification described below) will work fine for instructional purposes.

General Teaching Principles Note: For a look at some of the actual materials that I use in my map and compass classes, see Compass Techniques 1. When teaching map and compass, start with the basic idea of what a map is. Often, teachers will use the metaphor that a map is a representation of what one sees from an airplane, or "a view from above." This a suitable metaphor for the secondary grades and above, but for younger age groups, research by T. Ottosson (1988) indicates that the top down metaphor may be confusing. Instead, Ottosson found that referring to a map as "miniature world" provides a better basis for instruction. Young children already possess knowledge of the immediate world around them (the layout of the school and school yard and their neighborhood) and that understanding should be utilized as the starting point for map teaching. 2. For younger age groups, introduce the idea of directions and the purpose of a compass, but avoid getting into much detail about compasses. Compass bearings, the difference between magnetic north and true north are confusing, and it is best to concentrate on maps and how one can find their way using a map. Even at an advanced level, most orienteering is done without a compass, and navigation is accomplished primarily from map reading. 3. Use a combination of indoor and outdoor settings for teaching. Begin in the classroom with basic concepts and then move to the outdoors to actually use what students have learned. For an example, in my indoor session I introduce directions, compasses and how to set a bearing. I have the students set different bearings on their compass while still in the classroom. When everyone is comfortable with bearings, I move the class outdoors and have everyone participate in a three-leg compass walk (Kjellstrom, 1994).

Of all map and compass exercises, the three-leg compass walk is one of the best--and it can be done with nearly any age group. Start by having each student mark their location with a pencil or a small stick and setting their compasses to north (360 degrees). Once north has been set, they sight down the direction of travel arrow on the compass and pick out a landmark in the background. The landmark can be a tree, baseball backstop, a telephone pole, etc. The students then step out 100 paces. (These are double step paces. In other words, students should count each time their right foot touches the ground.) Everyone stops after 100 paces. The students are then directed to set their compasses to 120 degrees and they pace out another 100 steps and stop. Then everyone is directed to set their compasses to 240 degrees and pace out another 100 steps. At this point, they have completed walking a triangle and should end up fairly close to their starting point. The exercise quickly becomes a game among students to see how close they can come to their starting point.

Use easy to find locations to attach your control points: the corners of buildings, a basketball post, the intersection of two trails, a hill top, etc. No matter what the age group, on the first course, students should not have to use the compass to find the points. Wait until your students have done one or more courses before including any control points which require the use of a compass. Start slow and let success build upon success. 5. Use the utmost care when teaching about declination. In twenty years of teaching map and compass, I have found that of all map concepts, declination, the difference between magnetic north and true north, is the most difficult to teach. For younger groups, avoid the concept altogether. For older ages, at some point, you'll need to deal with declination since bearings taken in the field must be adjusted so that they can be applied to the map, and, conversely, map bearings need to be adjusted so they can be used in the field.

The confusion that can result from trying to remember when to add or subtract can literally bring a map and compass class to a halt. I've seen well educated individuals in map classes who have become so completely frustrated using the addition-subtraction method that they've been driven nearly to tears. A young woman--who later became my wife--was one of those, and she was one very good reason why I changed my method of teaching. The secret to avoiding these problems is to base all bearings on true north:

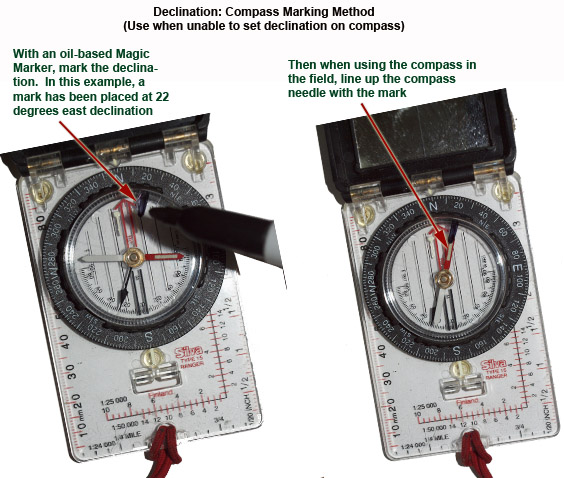

For example, if your declination is 10 degrees west, place a mark at 350 degrees (360 degrees minus 10 degrees). The usual procedure to take bearings in the field is to line up the compass needle with the orienteering arrow, but in this method the compass needle is lined up with the mark. This has the effect of making all compass bearings based on true north. Compass bearings may applied directly to the map, and map bearings may be used directly in the field. There is no subtracting or adding--or drawing lines on the map. Since the mark is in indelible ink, it can't be rubbed or washed off. It can, however, be removed with rubbing alcohol, or white gas (commonly carried on camping or backpacking trips) in the event that the user goes out of state to an area with a different declination. |

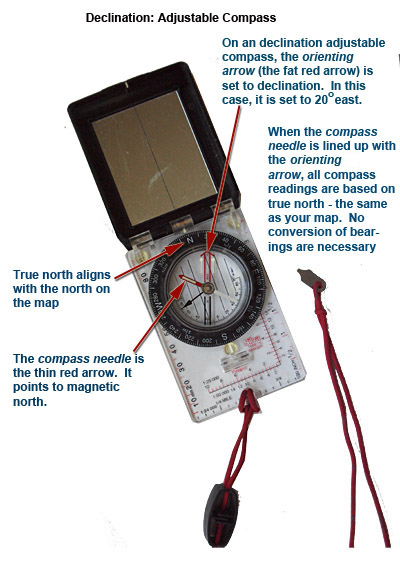

Adjustable Compass. The last method is the easiest. If you have a say in the type of compasses which are purchased for your classes, buy compasses in which declination can be set. All you do is to turn the declination adjustment screw on the compass and all readings are automatically converted to true north. There's no further bother. Both of these methods have worked well in my classes and have saved students from hours of frustration.

I use a two-hour course format for map and compass presentations to school children and scout groups. One hour of the class is spent indoors and the other hour is spent outdoors. Begin the class by passing out maps and discussing what a map is (using the "top-down" metaphor--or for young children, use the "miniature world." Discuss map symbols (roads, trails, buildings, lakes, rivers, etc.). Then bring up the idea of directions: the top of the map is north, bottom is south, etc. The compass comes out next. Show how compasses indicate north, south, east and west. Finally, explain how to set a bearing on the compass and how students follow bearings in the field. Practice setting a few bearings indoors. Next move outdoors and do the three-leg compass walk described previously. Two hours isn't much, but it is enough time to give your students an introduction to maps and compasses and pique their interest. After doing the compass walk, you'll find they'll be excited to try more. If you are able to fit another session into the schedule, you'll be able to go into more detail about maps, but always combine an indoor session with an outdoor session. There are other exercises similar to the three-leg compass walk which can be found in the books in the reference list accompanying this paper. Books: Maps for America, Reston, VA: US Geological Survey, 1982. A reference book for college level courses. It has useful templates for UTM coordinates, lots of charts and illustrations of the parts of Geological Survey maps. Kals, W.S., Land Navigation Handbook. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 2005. This well written book covers all aspects of maps and compasses. It gets my top rating as the best overall text for map and compass at the college level. Kjellstom, Bjorn. Be Expert with Map and Compass (rev. ed.). New York: Macmillan, 2009. Still in print, this is the standard map and compass text. It is particularly useful for school aged children and includes a number of games and exercises. Singleton, Robert. You'll Never Get Lost Again. New York: Winchester Press, 1979. Includes basic map information, but also takes a different approach, concentrating on finding oneself if lost. Barden, Cindy. Mighty Maps! Facts, Fun and Trivia to Develop Map Skills. New York: Lrnz Crprtn, 1997. This is children's learning book of maps. Here's some suggestions for other children map books: 3 Children's Books About Maps

Videos and Materials Available on the INTERNET: "Finding Your Way in the Wild." Richard Diercks Company, 1990. While this 35 minute video will not win any artistic awards, it does cover the basics well and is a good supplement to classroom work. "Finding Your Way with Map and Compass." This brief introduction to using maps and compasses is an on-line version of a booklet that the U.S. Geological Survey publishes. Includes text and graphics. Address: https://egsc.usgs.gov/isb/pubs/factsheets/fs03501.html "Beginning Guide to Orienteering." A very brief description of the sport of orienteering from the Orienteering USA Site: https://www.us.orienteering.org/new-o/beginners-guide "The Sport of Rogaining." What is rogaining? It's orienteering on steroids. It's a long, 24 hour- orienteering races done in teams. Here is more information from the International Rogaining Federation: https://www.rogaining.com/articles.html "Perry-Castaneda Library Map Collection." A comprehensive map holding at the University of Texas, Austin library. A number of maps are downloadable. Address: https://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/ "US Geological Survey: Maps, Imagery & Publications." The main U.S. government agency in charge of mapping and map services: https://www.usgs.gov/pubprod/ "Scientific Journal of Orienteering." This is a research oriented journal covering aspects of the sport of orienteering. An index to PDF's of the journal is found on the International Orienterring Federation website: https://orienteering.org/resources/publications/scientific-journal-of-orienteering/ . References Ottosson, T (1988). What does it take to read a map? Scientific Journal of Orienteering, 4, 97-106. Blades, M. & Spencer, C. (1989). Children's wayfinding and map using abilities. Scientific Journal of Orienteering, 5, 48-60. Kjellstrom, B. (1994). Be Expert With Map and Compass (rev. ed.). New York: Macmillan. Ratliff, D. (1964). Map, Compass and Campfire. Portland: Binfords and Mort. (Ratliff's book is the first in which mention is made of the simple but elegant method of compensating for declination by making a mark on the compass.)

[END] |

In the past--and many teachers still teach this way--declination was accounted for by using an addition-subtraction method. Whether to add or subtract depends on whether you live in an area with an east or west declination. Various memory techniques have been employed, including the commonly used rhyme: "East is least" (subtract declination from a compass bearing) and "West is best" (add the declination to compass bearings). This is true if you are converting from a compass bearing to the map, but if you are working from the map to a compass, you need to do just the opposite.

In the past--and many teachers still teach this way--declination was accounted for by using an addition-subtraction method. Whether to add or subtract depends on whether you live in an area with an east or west declination. Various memory techniques have been employed, including the commonly used rhyme: "East is least" (subtract declination from a compass bearing) and "West is best" (add the declination to compass bearings). This is true if you are converting from a compass bearing to the map, but if you are working from the map to a compass, you need to do just the opposite.