Important Conservationists Who Have Made Significant Contributions in Protecting Wilderness and Other Backcountry Areas

Outdoor adventure needs wilderness: areas of unspoiled nature. We looked at several individuals who made important contributions in politics, science and writing which led to the protection of forests, parks, wilderness areas, rivers, and wildlife refuges. Those included the following:

John Muir (Gilded Generation). John Muir's books were minor best sellers (you read a selection from one of John Muir's books). In the early 1900's, he wrote an article for the Century magazine which marked the beginning of the effort to protect Yosemite National Park. Earlier in life, he was an inventor but after an accident nearly blinded him, he took a long walk. Eventually, he found his way to California and spent many days hiking in the Sierras.

John Muir (Gilded Generation). John Muir's books were minor best sellers (you read a selection from one of John Muir's books). In the early 1900's, he wrote an article for the Century magazine which marked the beginning of the effort to protect Yosemite National Park. Earlier in life, he was an inventor but after an accident nearly blinded him, he took a long walk. Eventually, he found his way to California and spent many days hiking in the Sierras.

Theodore (Teddy) Roosevelt (Progressive Generation). President of the United States from 1901 - 1909. Roosevelt was noted for his energetic personality and range of interests and achievements. As a child, he was unhealthy, and largely stayed at home studying natural history. In response to his physical weakness, he embraced a strenuous life. He was admirer of John Muir and even spent time with him in Yosemite. He agreed with the writings of Fredrick Jackson Turner (below). While President, he set aside more national forests and wildlife refuges than any other single person in world history. Nearly every National Forest in Idaho was created by the pen of Roosevelt.

Theodore (Teddy) Roosevelt (Progressive Generation). President of the United States from 1901 - 1909. Roosevelt was noted for his energetic personality and range of interests and achievements. As a child, he was unhealthy, and largely stayed at home studying natural history. In response to his physical weakness, he embraced a strenuous life. He was admirer of John Muir and even spent time with him in Yosemite. He agreed with the writings of Fredrick Jackson Turner (below). While President, he set aside more national forests and wildlife refuges than any other single person in world history. Nearly every National Forest in Idaho was created by the pen of Roosevelt.

Fredrick Jackson Turner (Missionary Generation). Turner is not actually a conservation figure. He is a historian. But Turner laid some very important intellectual groundwork with a paper he wrote about the ending of the American frontier. He bemoaned the ending of frontier because wilderness was vital to the American experience. Wilderness, he wrote, fosters individualism, independence and the confidence that encourages self government. It is no mistake that democracy took hold in America. Wilderness, it comes to stand, is not only important from Muir’s point of view (revitalizing one’s soul and spirit), but it is also a part of the rise and embrace of democracy.

Fredrick Jackson Turner (Missionary Generation). Turner is not actually a conservation figure. He is a historian. But Turner laid some very important intellectual groundwork with a paper he wrote about the ending of the American frontier. He bemoaned the ending of frontier because wilderness was vital to the American experience. Wilderness, he wrote, fosters individualism, independence and the confidence that encourages self government. It is no mistake that democracy took hold in America. Wilderness, it comes to stand, is not only important from Muir’s point of view (revitalizing one’s soul and spirit), but it is also a part of the rise and embrace of democracy.

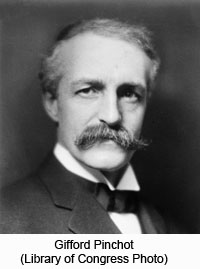

Gifford Pinchot (Missionary Generation). Pinchot is different sort of conservation figure. A graduate of Yale, he spent time in Europe, learning how they "managed" their forests and coming to believe that forests should also be managed in the U.S. He eventually became Chief of the Forest Service. He supported the idea of utilitarianism, better known these days as multiple use. That's in clear opposition to John Muir's belief. Muir was a preservationist. He wanted to save and protect wild lands. Pinchot wanted to use them for grazing, timbering, mining, recreational developments, etc.

Gifford Pinchot (Missionary Generation). Pinchot is different sort of conservation figure. A graduate of Yale, he spent time in Europe, learning how they "managed" their forests and coming to believe that forests should also be managed in the U.S. He eventually became Chief of the Forest Service. He supported the idea of utilitarianism, better known these days as multiple use. That's in clear opposition to John Muir's belief. Muir was a preservationist. He wanted to save and protect wild lands. Pinchot wanted to use them for grazing, timbering, mining, recreational developments, etc.

Aldo Leopold (Lost Generation). Leopold was raised in Iowa and worked for the Forest Service in New Mexico. Working within the system as a Forest Service employee, he sought a way to protect wild lands, and in 1924 his work led to the creation of the first administratively protected primitive area on the Gila National Forest. He was an ecologist and wrote the Sand County Almanac (one of your readings) which has became one of the most famous books on nature of all time.

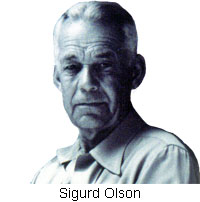

Sigurd Olson (Lost Generation). Sigurd Olson lived in Ely, Minnesota and taught at a Junior College there. In the summers, he guided canoe trips. He spent many years working to preserve the Boundary Waters Canoe Area, and is well known in the Midwest as the canoe country writer and philosopher. The selection on canoeing that you read was by Olson.

Sigurd Olson (Lost Generation). Sigurd Olson lived in Ely, Minnesota and taught at a Junior College there. In the summers, he guided canoe trips. He spent many years working to preserve the Boundary Waters Canoe Area, and is well known in the Midwest as the canoe country writer and philosopher. The selection on canoeing that you read was by Olson.

Olaus and Mardy Murie (Lost Generation). Murie was a naturalist, author, and wildlife biologist who did groundbreaking field research on a variety of large northern mammals. He is best known for his work with elk, and, in fact, is referred to as the "father of modern elk management." He also served as president of The Wilderness Society. With his wife, Mardie Murie, he successfully campaigned to enlarge the boundaries of the Olympic National Park, and to create the Jackson Hole National Monument and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. His wife, Mardy Murie took up many environment causes after Olaus died, and late in her life became known as the grand dame of wilderness movement. He and Mardie lived near Moose, Wyoming at the base of the Tetons.

Olaus and Mardy Murie (Lost Generation). Murie was a naturalist, author, and wildlife biologist who did groundbreaking field research on a variety of large northern mammals. He is best known for his work with elk, and, in fact, is referred to as the "father of modern elk management." He also served as president of The Wilderness Society. With his wife, Mardie Murie, he successfully campaigned to enlarge the boundaries of the Olympic National Park, and to create the Jackson Hole National Monument and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. His wife, Mardy Murie took up many environment causes after Olaus died, and late in her life became known as the grand dame of wilderness movement. He and Mardie lived near Moose, Wyoming at the base of the Tetons.

Robert Marshall (GI Generation). Marshal first worked in the Forest Division of Indian Affairs and then moved to the Forest Service. Since he came from a prominent and wealthy eastern family with political connections, he was effective in protecting additional Forest Service lands as wilderness. He is one of the founders of the Wilderness Society. One of their early causes was working for the protection of the Boundary Waters. He is known for his long hikes, and his death at an early age is sometimes attributed to the stress these hikes put on his heart. The Bob Marshall Wilderness Area in Montana is named after him.

Robert Marshall (GI Generation). Marshal first worked in the Forest Division of Indian Affairs and then moved to the Forest Service. Since he came from a prominent and wealthy eastern family with political connections, he was effective in protecting additional Forest Service lands as wilderness. He is one of the founders of the Wilderness Society. One of their early causes was working for the protection of the Boundary Waters. He is known for his long hikes, and his death at an early age is sometimes attributed to the stress these hikes put on his heart. The Bob Marshall Wilderness Area in Montana is named after him.

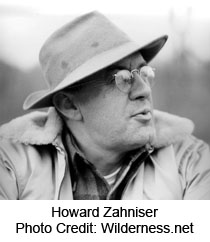

Howard Zahniser (GI Generation). Zahniser was the director of the Wilderness Society for many years. He was involved in the fight against the Echo Dam (in Dinosaur National Monument). He is best known for putting together the language of the Wilderness Bill which passed the U.S. Congress in 1964.

Howard Zahniser (GI Generation). Zahniser was the director of the Wilderness Society for many years. He was involved in the fight against the Echo Dam (in Dinosaur National Monument). He is best known for putting together the language of the Wilderness Bill which passed the U.S. Congress in 1964.

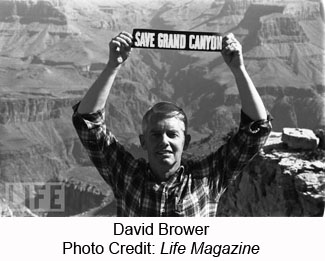

David Brower (GI Generation). Brower led the Sierra Club for many years. He was intimately involved in trying to prevent dams from being built in the Grand Canyon. Under his directorship the Sierra Club lost its tax exempt status, but its membership and influence swelled. As a result, he and other conservationists were successful in providing permanent protection for the Grand Canyon from dams.

David Brower (GI Generation). Brower led the Sierra Club for many years. He was intimately involved in trying to prevent dams from being built in the Grand Canyon. Under his directorship the Sierra Club lost its tax exempt status, but its membership and influence swelled. As a result, he and other conservationists were successful in providing permanent protection for the Grand Canyon from dams.

Return to: Outdoor Literature Course Main Page

[End]