______________________________________________________________________________

The Portal

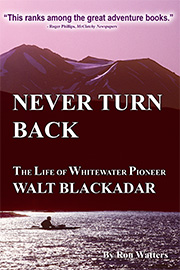

This is the first chapter from Never Turn Back: The Life of Whitewater Pioneer Walt Blackadar,

.

Copyright Ron Watters - All Rights Reserved. (Information on purchasing the book.)

THE cold, grit-filled water rumbled as it ground between the dark polished walls of the gorge. The half-mile-wide river funnelled into the canyon, and the current accelerated as it narrowed to half its width and then to half again and half once more until it stretched only 200 feet from bank to bank.

Insignificant in the midst of the gray river, a white object floated. Squeezed within the thin fiberglass walls of the 13-foot-long craft, a man with a red helmet paddled toward the portal of the gorge. The red helmet and the orange from his life jacket flashed the only warm colors present in the grim grayness. The man himself was dressed all in black, covered by a quarter-inch layer of neoprene to shelter his skin from the sharp biting cold of the river. He dipped the kayak paddle in one side and then on the other, alternating sides, propelling his boat ever nearer to the rumble. The rhythmic motion of his arms was the only human movement for a hundred miles.

Insignificant in the midst of the gray river, a white object floated. Squeezed within the thin fiberglass walls of the 13-foot-long craft, a man with a red helmet paddled toward the portal of the gorge. The red helmet and the orange from his life jacket flashed the only warm colors present in the grim grayness. The man himself was dressed all in black, covered by a quarter-inch layer of neoprene to shelter his skin from the sharp biting cold of the river. He dipped the kayak paddle in one side and then on the other, alternating sides, propelling his boat ever nearer to the rumble. The rhythmic motion of his arms was the only human movement for a hundred miles.

A vast scale of inconceivable proportions rose above him, a monstrous scale of the towering icy mountains of the Saint Elias Range, standing like giant transfixed souls shrouded in white; and slipping slowly downward between the white shrouds moved great masses of glacial ice groaning and cracking, flowing toward the river. To his right the glacier snapped, and another house-sized slab of ice slapped against the river and joined him as an unwanted companion while the water raced into the canyon.

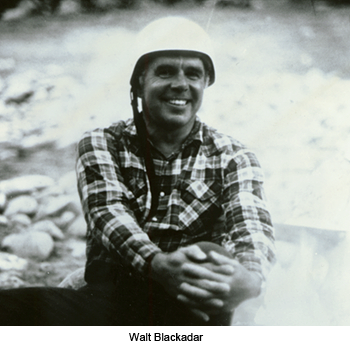

It was early in the day on August 25, 1971, when Walt Blackadar entered Turnback Canyon on the Alsek River. He was a doctor from a small town in Idaho. Originally from the East, he moved his family west shortly after the war so he could be near hunting and fishing. Forty-nine years of age, he had only started kayaking four years earlier, yet with each stroke of his paddle he edged nearer to the start of the most difficult stretch of big whitewater ever attempted by anyone.

There was something incredible in the fact that he was there in the first place. He wasn't much of an athlete. He had done some wrestling in high school and certainly he was endowed with strong shoulders, but otherwise he wasn't impressively built nor a particularly attractive man, lacking the smooth muscular look of young, fit world champion kayakers. He was short, had a slight paunch and lacked an athlete's endurance. He mostly kept in shape after his long days at his medical office by working on his ranch and doing a little hunting, hardly the kind of fitness program one would expect in preparation for attempting one of the world's great unrun stretches of whitewater.

On top of that, he had little information to go on. Only a few parties had ventured down the river, and when these early explorers had scampered up to the icy edge and peered down upon the furious torrent of water cascading through Turnback Canyon, they quickly understood the danger and arduously carried their boats and equipment around on the glacier. Blackadar had been told that trying to run the canyon was foolish and impossible. So why was he now attempting it?

He had, at least, hedged his bets somewhat before starting. He was adventurous, but not foolish. Five days earlier, he had reconnoitered the canyon from the seat of a fixed-wing plane. Carefully looking at the rapids below, he could see that the waves appeared huge, perhaps as high as 20 feet, but he could see nothing that from his experience was virtually impossible.

Difficult? Certainly. Exceedingly difficult? Yes, that it most accurately was-and is. He knew that looking at the river from 500 to 800 feet in the air is deceiving. Once a kayaker gets to river level, rapids that appear harmless from above can be death traps. He would cautiously enter the canyon, he had planned, and get out of his boat, scouting here and there, looking at the rapids. If he saw anything too dangerous, he would carry his boat around.

It was a sensible plan, but the normal standards of river running did not apply here. The water raged between the narrow walls of Turnback Canyon with more raw power, more exhausting frigidity, and more frightening turbulence than anything in his experience. Though he didn't fully realize it at the time, the challenge he faced would in time represent the Everest of the whitewater world. It took years of probing Everest with teams of mountaineers before it was climbed, and then more years of team ascents before it was climbed solo. Walt Blackadar was making the first attempt at whitewater's Everest, and he was making the attempt alone.

He reached the point of no return. The current dashed him between the twisting canyon walls. He paddled up over building swells of water. The bow of the kayak rose and fell, rose and fell. Cold icy water splashed over him as he struggled to keep upright. The pace quickened, and his boat, like a mouse tossed between the paws of a cat, reeled from side to side. "I was in a frothy mess that was far worse than I've seen," he wrote. "[It was] like trying to run down a coiled rattler's back, the rattler striking me from all sides . . . . I skidded and swirled and turned down this narrow line."

He held on, trying to survive the powerful grip of the river. Busy with the business of survival, he had little time to reflect why he was there. He had mentioned in his diary of the trip that he got depressed watching patients with incurable diseases and that he wasn't getting any younger. He refused to retire from his manhood into what Steinbeck called "a kind of spiritual and physical semi-invalidism."

Invalidism. It was a chilling word to Blackadar. He wanted nothing to do with it. In his work, he had seen it all too frequently. And he had seen its menacing shadow descend upon his father. He wondered why his father couldn't fight back. "A kind of second childhood," said Steinbeck, "falls on so many men. They trade their violence for the promise of a small increase of life span." Blackadar held fast to his violence like a miser; no, more like a boxer fighting his way out of a corner, but he had picked some place to stage his fight.

Perhaps he really didn't know why he was there. He knew, simply, that he must try. And try he must, for he was in for the ride of his life. Powerful whirlpools, back-rushing walls of water and vicious holes lay in his path below. He hadn't even begun to face the full fury of the river. If he faltered-or even if he did everything right, but had bad luck-the current could tear him from his boat and he would die. Conrad put it aptly: "An elemental force is ruthlessly frank." To survive the forces of Turnback he must not leave the protection of his boat. Indeed, in his own words, he was "caught up in a hell of whitewater."

Elemental forces had always captivated him. He found a certain sensual pleasure and heightened sense of self-mastery from paddling a canoe across a stormy, white-capped lake, stalking an elk in a snowstorm, or maneuvering a raft over a waterfall. He was motivated by the problem and risk posed by an obstacle and was stimulated by surmounting it, the tougher and more physical the effort, the better. His attempt on Turnback Canyon was an extension of this need to test himself, to arouse his sensibilities, carried to an extreme.

In a sense, Blackadar's run of Turnback Canyon is a metaphor for his own life. Even the word "Turnback" is so accurately representative of what he sought to overcome that a Hollywood script writer couldn't have thought of a better appellation. There could be no turning back for Blackadar. The powerful motivating forces which brought him to face the treacherous waters of Turnback Canyon are the same which drove him relentlessly through his life.

And except for one raw, trying day when youth swirled past his reach, he never looked back, he never turned back.

[End of "The Portal" Chapter]

More Information: Never Turn Back Main Page OR Information on Purchasing OR List of Other Books by the Same Author

Never Turn Back: The Life of Whitewater Pioneer Walt Blackadar

Table of Contents

Prologue: The Portal • Chapter 1: Salmon City • Chapter 2: The Middle and the Main • Chapter 3: Esquimautage • Chapter 4: Emergency Call from North Fork • Chapter 5: A Look in the Mirror • Chapter 6: "In the Gorge and Stranded" • Chapter 7: The Big Su • Chapter 8: Tragedy on the West Fork • Chapter 9: The Biggest Ride • Chapter 10: On the Edge • Chapter 11: I'll Be Back • Chapter 12: Through the Night • Chapter 13: River of No Return • Epilogue • Acknowledgments • Source Notes • Index

(Maps of Idaho and Alaska and 16 pages of photographs appear between pages 120 and 121.)

More Information: Never Turn Back Main Page OR Information on Purchasing OR List of Other Books by the Same Author

Other Top Rated Books:

Kath and Ron's Guide to Idaho Paddling: Flatwater and Easy Whitewater Trips

Never Turn Back is published by

![]() The Great Rift Press: A Part of the Great Rift Company

The Great Rift Press: A Part of the Great Rift Company

[END]