Copyright & Revisions: Copyright © 1997. Reformatted in 2013 and minor revisions were made to the text.

Publication History: Originally published in the Proceedings and Research Symposium Abstracts of the 19th Association of Outdoor Recreation and Education (AORE) Conference. Citation for the original paper: Watters, R. (2006). Generational analysis: A new method of examining the history of outdoor adventure activities and a possible predictor of long range trends . In Turner, J (Ed.). Proceedings and Research Symposium Abstracts of the 19th Association of Outdoor Recreation and Education (AORE) Conference (pp. 76-102). Boise, ID: The Association of Outdoor Recreation and Education.

Reproduction Information: You are welcome to provide links to this page or to use short quotations and paraphrases in other documents as long as they appropriately reference the source. There is no charge for non-profit organizations to reproduce or publish extensive parts or all of this paper, but please obtain advanced permission from Ron Watters (wattron@isu.edu). Photo credits: Ron Watters.

Abstract

This is an examination of the history of outdoor adventure by the use of generational analysis. The importance of generations in American history was brought to the forefront by William Strauss and Neil Howe in their ground breaking work Generations: The History of America's Future, 1584 to 2069. Strauss and Howe suggest that history is a succession of generations, and that each generation belongs to one of four types which repeat sequentially in a fixed pattern. When historical events in outdoor adventure are examined in this same generational context, a similar repetitive pattern also exists. Thus, the possibility exists that generational analysis could be used as a predictor of long range trends.

Definitions Definition of Outdoor Adventure. Outdoor adventure can have many different definitions, but for the purposes of this investigation it is defined as largely non-motorized in nature. It involves little or no alteration of the environment. Outdoor adventurers live close to the environment and accept natural forces as part of the experience. Appreciation of the natural world is a part of the experience. Outdoor adventures take place primarily, but not exclusively in remote backcountry, wilderness and undeveloped areas. Such adventures do not involve man-against-man as in warfare. They do, however, often pit men and women against natural forces. Outdoor adventures under this limited definition are done for the hunger of adventure and not to obtain or pave the way for wealth, to conquer foreign lands or to secure religious converts.[4] Examples of outdoor adventure endeavors include: arctic exploration, sailing journeys, rock climbing, mountaineering, cross-country and back-country skiing, backpacking, canoeing, kayaking, whitewater river running, and adventurous biking. Modern Age of Adventure. The term "Modern Age of Adventure" can be interpreted in different ways, but for the purposes of this study, it is defined as a period of time starting in the early to mid 1800s and extending to the present. From an historical perspective, the early and mid nineteenth century marks an important change in attitude about adventure and exploration. Not all, but most previous exploration was undertaken for exploitation. The Modern Age of Adventure begins when explorers went exploring for the sake of exploration—not for financial gain, not for colonial expansion, and not for the purpose of religious conversion. There always have been individuals in history who have been motivated purely by adventure, most certainly, but for the great bulk of explorers prior to the Modern Age of Adventure, other materialistic rewards loomed larger. The early 1800s represent a watershed, a turning of the tide. The Modern Age is similar in some respects with what historian William H. Goetzmann calls the "Second Age of Discovery."[5] Both were possible because of developments in literature, science and the arts. But they are different. Goetzman's Second Age begins at least a hundred years earlier and encompasses exploration and discovery on behalf of science. It was the Enlightenment, the turn away from superstition and irrationality, which paved the way for the Second Age. On the other hand, it is the Romantic Movement with its emphasis on nature which cleared the way for the Modern Age. The Modern Age is also limited to outdoor adventure activities (as defined above). Science may play a role in an adventurous activity—and science may even be used to give it legitimacy—but the underlying motivation for the activity is adventure. Since this investigation covers a time period encompassed by the Modern Age of Adventure, ten generations from the late 1700s to present, were identified and studied.

Spiritual awakenings, on the other hand, are periodic times in history when there is a society wide interest in self-examination: finding meaning or seeking a higher purpose in life. An example is the Boom Awakening which occurred during the 1960s and early 1970s. During this time, many young people were involved in what might be described as inner journeys directed toward greater personal understanding. Some experimented with mind-altering drugs. Others joined communes or took up studies of eastern religions. And, yes, still others found transitory meaning in nature and outdoor activity.

Life Phases. Another concept which is helpful in understanding generational history is that of life phases. When you think of a generation, at any point in time during the life span of the generation, its members will be in one or more life phases. Strauss and Howe argue that a generation assumes a collective identity based on the relationship between life phases and social movements. More on that in the next section, but let's first take a look at the definitions of each life phase (pp. 60-61): Table 2: Life Phases

Basic Generational Types. Straus and Howe's most important observation is that when American history is viewed through a generational lens, four distinct generational types become apparent. The four generational types are Idealist, Reactive, Civic and Adaptive (p. 64). As alluded to above, the generational type that a particular generation assumes is governed by where it lies in relation to a social movement. For example, if a generation's "rising adults" phase occurs during a spiritual awakening, the generation will be of the Idealist type.[8] Since generational types depend upon social movements, and social movements occur in a regular pattern, the generational types also occur in a regular pattern:

Given that life phases are approximately 22 years in length, new generational types occur approximately every 22 years. This regular repeating pattern of generation types is referred to by Strauss and Howe as the Four Part Cycle (p. 75).

Generations in American History With this background, let's take a look at specific generations identified by Strauss and Howe. As mentioned above, it is not necessary to go back in history to the 1500s. Rather, from the context of this paper, we'll concentrate on generations beginning with the Modern Age of Adventure in the early 1800s. The years shown in parenthesis, below, are birth years.

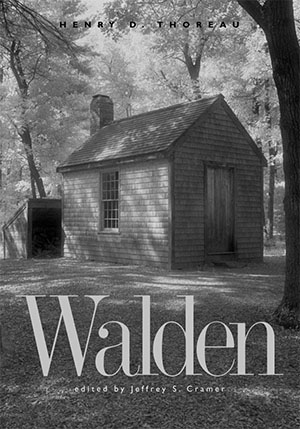

Men wanted for Hazardous Journey. Small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful.[15]The ad may be apocryphal, but, nonetheless, it indicates the modern attitude to exploration. Those undertaking such an adventurous journey can't expect a king's ransom. In fact, all they can really expect is a "small" wage, likely earning less than if they stayed home and worked. But challenge and adventure? Oh yes. That they can expect. Concurrent with this change in attitude, there's also a change brewing in the public's attitude to toward uncivilized lands. Roderick Nash in Wilderness and the American Mind points out that when we look at history, wilderness was the primary adversary of civilization. The wilderness—the wild outdoor environment—was the villain. But wilderness was conquered fairly quickly in the United States. As the frontier disappeared, there was a growing realization that wilderness wasn't something to be conquered and eliminated but something to be embraced. [16]  Some, such as Frederick Jackson Turner, the eminent historian, even argued the relationship between people and the frontier and the presence of wild lands played a vital role in fostering the American ideals of self government and democracy.[17] As wilderness was tamed and heretofore wild lands went under the plow or fell to the axe, the national mind-set shifted from wilderness as a burden to wilderness as beneficial. Wilderness no longer was a place to be feared. It was a place to be enjoyed—and it was a place to test oneself, a place where adventures may take place. It was no longer necessary to conquer wilderness but rather live with it and reap its benefits. Some, such as Frederick Jackson Turner, the eminent historian, even argued the relationship between people and the frontier and the presence of wild lands played a vital role in fostering the American ideals of self government and democracy.[17] As wilderness was tamed and heretofore wild lands went under the plow or fell to the axe, the national mind-set shifted from wilderness as a burden to wilderness as beneficial. Wilderness no longer was a place to be feared. It was a place to be enjoyed—and it was a place to test oneself, a place where adventures may take place. It was no longer necessary to conquer wilderness but rather live with it and reap its benefits. Lastly, the Modern Age of Adventure begins at a time when change is afoot in the literary world. In a word it's transcendentalism. The American transcendental movement began in the early 1800s as a controversy in the Unitarian Church. In accordance with Unitarian beliefs, the pathway to God led through study of the scriptures and by doing good works, a sort of a rule-book approach. Follow the rules and you'll find God. Some Unitarian ministers, however, felt that there must be more than following rules and doing good works, that understanding of God must be something that was felt. Man was capable of much more, they said, including imagination and intuition. Most importantly, one could experience the divine through direct contact with nature.[18] The most well known of the transcendentalists was Ralph Waldo Emerson, and since the natural world played such an important role in transcendentalism, it is no surprise that one of his best known works is a series of essays entitled Nature.[19] While Emerson wrote theoretically about transcendentalism, Henry David Thoreau took things a step further. He sought to employ transcendental principles in every day life. To do so, he built a cabin along the shores of Walden Pond, and there for two years he lived, spending time close to nature, and discovering for himself divine truths. If any one event stands as a symbolic beginning of the Modern Age of Adventure, it is the publication of Thoreau's Walden in 1854.  Walden encapsulates the modern approach to the outdoors. If adventure is no longer undertaken taken for money or to conquer lands, then there had to be other reasons. Thoreau offers those reasons. Living fully and deliberately: "I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life." For quality of life: "To affect the quality of the day, that is the highest of arts." For nature's beauty: "Heaven is under our feet as well as over our heads." To live independently: "If man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer." To find spiritual truths. To live one's dreams. To live simply. And more. It's all there in Walden. If you read adventure literature, and look at what authors use to justify his or her forays to wind-swept mountain summits, untamed rivers and remote seas, you'll find underlying many of them Thoreau's ideas.[20] Walden encapsulates the modern approach to the outdoors. If adventure is no longer undertaken taken for money or to conquer lands, then there had to be other reasons. Thoreau offers those reasons. Living fully and deliberately: "I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life." For quality of life: "To affect the quality of the day, that is the highest of arts." For nature's beauty: "Heaven is under our feet as well as over our heads." To live independently: "If man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer." To find spiritual truths. To live one's dreams. To live simply. And more. It's all there in Walden. If you read adventure literature, and look at what authors use to justify his or her forays to wind-swept mountain summits, untamed rivers and remote seas, you'll find underlying many of them Thoreau's ideas.[20] Thus, Thoreau and those of his generation—Ralph Waldo Emerson and others—become the starting point of this study of generations and the outdoors. Dominant Outdoor Types. As we've learned from Strauss and Howe's work, generations fall into one of four types. Since each type has a distinct set of characteristics, it might then follow that certain types are associated with a higher level of interest in outdoor adventure. In fact, from my initial—albeit still incomplete—review of literature, personalities and historical events, two generational types do stand out as outdoor oriented. Those types are Idealist and Reactive. There is, however, a difference between the two in their respective approach to the outdoors. Idealist Type - In this generational type, interest in the outdoors is motivated by a desire to escape from civilization and get back to nature. For them, the inner journey is as important or more important than the outward one. Although competition clearly is present, it is often downplayed or not acknowledged. The Idealist generation approaches outdoor experiences with almost a religious zeal and is at times overly moralistic. While risk and challenge play a role, they are subverted by a larger sense of the wholeness and purity of the experience. Since the preceding two generations have little interest in the outdoors, they often feel, incorrectly, they have discovered outdoors. Reactive Type - This is clearly a risk taking generation. Risk, challenge and adrenaline are important motivators for participating in outdoor activities. They find talk about the spirituality of outdoor experience and the moralizing of the Idealist generation a bit tiresome. They'd rather get out and "just do it." Competition is embraced. They make a sport of almost every outdoor activity. There is less of a need to escape civilization, and the individual parts of the outdoor experience are as important as whole. A satisfying outdoor experience by the Reactive type can be had by playing in a wave along side a highway or climbing on a boulder from the back of a pick-up truck.

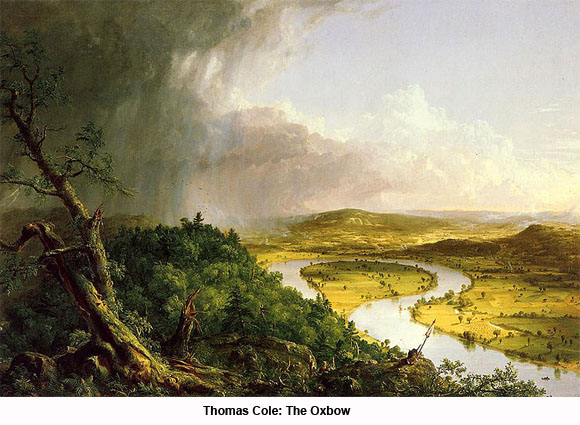

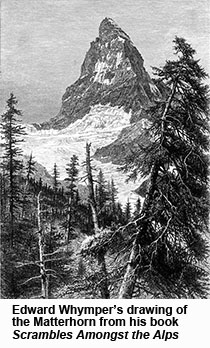

Recessive Outdoor Types. While Idealist and Reactive types flock to the outdoors, the level of interest in outdoor activities appears to wane in the Civic and Adaptive generational types: Civic Type. Members of this generation have little time for outdoor activities. They are a busy, productive generation. Early in adulthood, they are faced with overcoming a secular crisis which has threatened their way of life, and once the crisis has been overcome, they quickly settle into re-building and creating new institutions. They are team-oriented, and not particularly interested in individualistic endeavors, nor are they interested in spiritual experiences through outdoor activity. Moreover, they are not significantly motivated by risk. They already have enough risk in their lives and do not need to artificially create it by engaging in risky outdoor activities. Adaptive Type. Of all the generational types, this one is the most risk adverse. Security and conformity are important to them and there is little collective desire to engage in adventurous outdoor activities. Those who do break the mold and do take risks are seen as odd. Their children, however, will re-kindle a resurgence of interest in the outdoors and will see the non-conformists of their parent's generation as heroes. Introduction to Outdoor Generation Profiles The Outdoor Generation Profiles chart found in the later part of this paper summarizes each of the generations beginning with the Modern Age of Adventure. The first generation profiled is the Transcendental Generation. Since it is an Idealist generational type, you would expect cohorts of this generation to break away from the old ways, and encompass a new set of values, and seek personal fulfillment. Thus, it is this generation where it all begins and they pave the way for future adventurers. Drawing from the Romantic movement, and, most particularly, transcendentalism, Emerson and Thoreau laid out a philosophical framework. Thoreau, himself, engaged in the Walden experiment by living in communion with nature. While he didn't completely escape civilization, he tried to limit its influences as much as possible. During Thoreau's days, we don't see much of a rise in increase in outdoor activity among the lower or middle class. That, of course, is to be expected. There simply isn't much leisure time in the 1800s, and most people are busy making a living. It is interesting to note, however, that Thoreau was of the middle class. He did have to make a living by surveying and working in his father's pencil factory. Yet, he still managed go on boat trips, hike and climb in wild areas, and spend two years in cabin along Walden Pond. In addition to the literary world, American artists are also celebrating wilderness as an important aesthetic. Transcendental Generation artists such as Thomas Cole and Fredrick Church are painting the first purely wilderness scenes. While Strauss and Howe's work has been done on American generations, we can see parallels in Great Britain and Europe where democratic ideals are gaining cachet. In mid 1800s in Great Britain, it is the members of the Transcendental Generation who moved mountaineering from complete obscurity into something of an outdoor sport. While still considered oddities among their non-outdoorsy peers, these earlier mountaineers, nonetheless, attract begrudging admiration and respect for their adventurous activities.[23] With rudimentary skills, knowledge and equipment, they make a number of notable ascents in the Alps. The next generation (the Gilded Generation) will quickly take over, refine those skills, and, with a sudden burst of energy and verve, climb a dizzying array of Alpine summits.  The second generation profiled is the Gilded Generation, a Reactive Type. They are the risk takers. The previous generation has preached to them and held them to high standards, but they just wanted to break way and have a little fun. Part of that fun came through risky outdoor activities. In the Gilded Generation, we see an explosion of climbing in the Alps. They were primarily the climbers of the Golden Age of Mountaineering, generally dated from 1854 to 1865. Edward Whymper, a Gilded member, is the first to climb the Matterhorn.[24] In the U.S., John Muir is from the Gilded Generation. And nobody immersed himself in the wilderness experience more than John Muir. Muir often told the story that when he got off the boat in San Franscico in 1868, he asked which way to wild country. A man pointed to the east—and Muir started walking—all the way across the flower strewn (and still undeveloped) Central Valley and into the mountains he would later call the Range of Light.[25] While Muir describes his experiences in eloquent, poetic passages, his fellow artists of the Gilded Generation move beyond the security of the East and paint the American West. Painter Thomas Moran creates huge canvases of Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon while Albert Bierstadt captures the beauty of the Wind Rivers, Yosemite and the Sierras. The second generation profiled is the Gilded Generation, a Reactive Type. They are the risk takers. The previous generation has preached to them and held them to high standards, but they just wanted to break way and have a little fun. Part of that fun came through risky outdoor activities. In the Gilded Generation, we see an explosion of climbing in the Alps. They were primarily the climbers of the Golden Age of Mountaineering, generally dated from 1854 to 1865. Edward Whymper, a Gilded member, is the first to climb the Matterhorn.[24] In the U.S., John Muir is from the Gilded Generation. And nobody immersed himself in the wilderness experience more than John Muir. Muir often told the story that when he got off the boat in San Franscico in 1868, he asked which way to wild country. A man pointed to the east—and Muir started walking—all the way across the flower strewn (and still undeveloped) Central Valley and into the mountains he would later call the Range of Light.[25] While Muir describes his experiences in eloquent, poetic passages, his fellow artists of the Gilded Generation move beyond the security of the East and paint the American West. Painter Thomas Moran creates huge canvases of Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon while Albert Bierstadt captures the beauty of the Wind Rivers, Yosemite and the Sierras. The Progressive Generation (Adaptive type) follows the Gilded, and about the time they reach adulthood, we see a considerable drop in outdoor activity. (Normally, the Civic type would be expected to follow a Reactive type, but as noted above, the Civil War caused in break in the pattern.) Such a drop in outdoor interest would be expected from an Adaptive Generation. Unlike the Reactive Type, they tend to shy away from adventurous activities. There are exceptions, of course, such as Teddy Roosevelt's adventures in the Dakotas, but Roosevelt is an exception rather than the rule. A spurt of outdoor activity would be expected in the following generation: the idealists of the Missionary Generation. And, indeed, the historical record is clear on this account. This is golden age of arctic expedition: Scott and Admundsen race to the South Pole. Shackleton's ship Endurance is caught in the ice of Weddell Sea, and he undertakes a daring escape from Elephant Island. The Grand Teton is climbed for the first time. Included on the summit team appropriately enough for the Missionary Generation is an ordained minister. And the highest peak in Canada, Mt. Logan is climbed. The Lost Generation (Reactive) steps up to the plate next. These are the risk takers. Their most famous member from an outdoor adventure perspective is George  Mallory. We also see some real thinkers emerge from this generation whose work will have a lasting impact on the outdoor activity for years to come. Kurt Hahn, the founder of the Outward Bound movement is from this generation. Sigurd Olson, the bard of the Canoe country comes from this generation. So does Aldo Leopold, who through his simple but brilliantly written Sand County Almanac popularized the concepts of ecology and advanced scientifically sound reasons for preserving wilderness. Mallory. We also see some real thinkers emerge from this generation whose work will have a lasting impact on the outdoor activity for years to come. Kurt Hahn, the founder of the Outward Bound movement is from this generation. Sigurd Olson, the bard of the Canoe country comes from this generation. So does Aldo Leopold, who through his simple but brilliantly written Sand County Almanac popularized the concepts of ecology and advanced scientifically sound reasons for preserving wilderness. We would expect in the Lost Generation a significant increase in the outdoor interest from the previous generation, but that was limited greatly by world events. The prime of their lives came at an unsettled time during and after World War I. In Europe, an entire generation was almost wiped out in the killing fields of the war. In the US, the period of euphoria following World War I was dashed when the country fell into and was gripped by the Great Depression. A retraction in outdoor interest occurs in the following two generations: GI (Civic) and Silent (Reactive). The GI generation was busy fighting World War II, and when the soldiers returned, all attention was focused on starting families and building businesses and educational and governmental institutions. The Silent Generation settled into a cozy lifestyle. Safety and security was venerated and there is not much interest in adventure. To be sure there are some individuals who broke the mold, but they are clearly considered odd ducks. For example, Betty Woolsey who was backcountry skiing in the Jackson Hole area said that the townspeople thought she and her similarly inclined friends "were out of our minds. If anyone climbed to go skiing, they had to be crazy."[26] Jim McCarthy, former president of the American Alpine Club said the same thing about climbing: "[I]n those days [1940s], climbing was considered really strange. It was still like that when I started to climb in the Shawangunks in the 1950's. [Y]ou couldn't tell anyone you climbed. They'd look at you like you were really crazy, really nuts…."[27] Other oddities from this generation include Edward Abbey, Willie Unsoeld, Jim Whittaker, and Yvon Chouinard. While thought as of odd among cohorts of their generation, they would be held in esteem by the coming Boom Generation. Interest in outdoor activities swings back into vogue with the next two generations. The Boom Generation lives up to its name and adventurous outdoor sports boom like never before. Things boom even more as Generation X grows in adulthood. With their penchant for risk, Gen-X'ers climb harder routes and run tougher rivers, easily beating boomers at their own game. Outdoor Generation Profiles The following chart lists a series of individuals which were studied during the course of this investigation. They were selected for noteworthy contributions to outdoor adventure whether it was through literature, art or adventurous activity. This list is by no means complete. Certainly modifications and additions are in order, but it provides a starting point and the beginning of a cross-sectional view of outdoor history through eyes of the generations. The chart lists each generation starting with the Transcendental Generation. Under each generation is its identifying generation type as assigned by Strauss and Howe and a short description of its outdoor profile. This information is followed by the representative members of the generation, birth and death years, and associated outdoor-related literature and art.[28] Transcendental Generation (b. 1792-1821) Generation Type: Idealist Outdoor Profile: Budding interest in the appreciation of outdoors & outdoor activity Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) Writer: Walden. Thomas Cole (1801-1848) Father of the Hudson River School of Painting: Landscape with Tree Trunks, etc. Gilded Generation (b. 1822-1842) Generation Type: Reactive Outdoor Profile: Golden age of mountaineering & exploration of the American West Mark Twain (1835-1910) Writer: Roughing It, etc. Edward Whymper (1840-1911) Climber & Writer: Scrambles Amongst the Alps. John Wesley Powell (1834-1902) Explorer: The Exploration of the Colorado. Isabella Bird (1832-1904) Adventure Travel & Writer: A Lady's Life in the Rocky Mountains. John Muir (1838-1914) Mountaineer & Hiker: Steep Trails, etc. Albert Bierstadt (1820-1902) Painter: "Wind River Country," "Buffalo Trail." Thomas Moran (1837-1926) Painter: "Grand Canon of the Yellowstone," "Chasm of the Colorado." Progressive Generation (b. 1843-1859) Generation Type: Adaptive Outdoor Profile: Outdoor interest wanes Fanny Bullock Workman (1859-1925) Bicyclist & Climber. Sets female elevation record. Missionary Generation (b. 1860-1882) Generation Type: Idealist Outdoor Profile: Great interest in outdoor adventure and exploration Mary Kingsley (1862-1900) Adventure Travel: Travels in West Africa. Alexandra David-Néel (1868-1969) French explorer, visited Lhasa, Tibet in 1924. Fridfjof Nansen (1861-1930) Norwegian arctic explorer: First Greenland crossing. Farthest north, 1895. Fredrick Cook (1865-1940) Attempted Mt. McKinley. Arctic expeditions in 1891-92, 1897-99, 1908. Robert Falcon Scott (1868-1912) Arctic Explorer: Journals of Robert Falcon Scott. Roald Amundsen (1872-1928) Arctic Explorer: First to reach the South Pole. Robert Service (1874-1958) Poet of the Klondike gold rush: The Call of the Wild. Jack London (1876-1916) Writer: To Build a Fire. Sir Ernest Shackleton (1874-1922) Arctic Explorer: Arctic seas open boat journey. Sir Douglas Mawson (1882-1958) Explorer: First to reach the magnetic south pole. Albert McCarthy (1876-1956) Leader of first ascent of Logan. Following year, went to Alps and made 100 ascents. Franklin Spaulding (1865-1914) Leader of the first Grand Teton Ascent. Lost Generation (b. 1883-1900) Generation Type: Reactive Outdoor Profile: WW I causes an interruption in exploration, but interest remains and some notable personalities, writers and spokesmen emerge George Mallory (1886-1924) Explorer & Climber. Disappeared on Everest. Kurt Hahn (1886-) Founder of Outward Bound. Aldo Leopold (1886-1948) Outdoorsman & Writer: Sand County Almanac. Sigurd Olson (1899-1982) Canoeist & Writer: The Singing Wilderness. Phyllis Munday (1898- 1990) Famous Canadian climber. Commemorated on a 1998 postal stamp. GI Generation (b. 1901-1924) Generation Type: Civic Outdoor Profile: Members of the GI Generation are fighting a war and building institutions. Except for some notable exceptions, over-all public interest in outdoor activities wanes Sir Edmund Hillary (1919-) First to reach the summit of Everest and return, 1953. Paul Petzoldt (1908-1999) Well known American mountaineer. Teton & Himalayan climber. Walt Blackadar (1922-1978) One of the whitewater world's most famous personalities. Betty Woolsey (1913-1997) Climber and backcountry ski pioneer in the Tetons. Monica Jackson (1920-) Member of the first all-women's expedition to Himalayas in 1955. Colin Fletcher (1922-) Backpacker & writer: The Man Who Walked Through Time. Silent Generation (b. 1925-1942) Generation Type: Adaptive Outdoor Profile: Over-all public interest in outdoor activities continues to drop as the country settles into a quiet, conformist mood. Edward Abbey (1927-1989) Writer. Desert Solitaire. Jim Whittaker (1929-) First American to climb Everest - 1963 (A Life on the Edge). Willie Unsoeld (1926-1979) Pioneered the West Ridge of Everest during the 1963 American Expedition. Yvon Chouinard (1938-) Prominent climber and outdoor businessman. Founded Patagonia. (Climbing Ice). Boom Generation (b. 1943-1960) Generation Type: Idealist Outdoor Profile: Sharp growth in outdoor activities, and interest in nature and wilderness Jon Krakauer (1954-) Mountaineer and writer, Into Thin Air Scott Fischer (1956-1996) Mountaineer & owner of Mountain Madness Reinhold Messner (1944-) First to climb all 8,000 meter peaks without oxygen. Wanda Rutkiewicz (1943-1992) Legendary woman climber. First woman to climb K2. Rob Lesser (1945-) Renowned big water kayaker. First Inductee to Whitewater Hall of Fame. Terry Tempest Williams (1955-) Prominent woman nature writer from Utah. (Refuge). Annie Dillard (1945-) Prominent nature writer. (Pilgrim at Tinker Creek). Whit Deschner (1948- ) Whitewater kayaker and humorist. (Does the Wet Suit You?). Generation X (b. 1961-1981) Generation Type: Reactive Outdoor Profile: Participation levels continue to increase and risk level increases greatly Pam Houston (1962-) Short story writer. (Cowboys are My Weakness) Mark Twight (1961-.) Extreme climber & mountaineer. (Kiss or Kill: Confessions of a Serial Climber) Lynn Hill (1961-) Rock Climber. First free ascent of El Capitan's Nose in Yosemite. Hans Florine (1964-) Speed Climber. (Speed Climbing: How to Climb Faster and Better) Göran Kropp (1966–2002) Biked from Sweden, soloed Everest without oxygen, rode home. Millennial (b. 1982 -) Generation Type: Civic Outdoor Profile: Interest in outdoor activities is projected to wane (See discussion below). The Future At the time of this paper, the first cohorts of the Millennial Generation are moving into adulthood. It’s a bit too early to clearly describe a collective outdoor persona, but we can make some projections based on previous generational patterns. Strauss and Howe argue in History of America's Future that the Millennial Generation will be of a Civic type, and their argument is given further credence in their more recent work Millennials Rising.[29] If, indeed, that is the case then we can expect a retraction in interest in outdoor activities. All evidence thus far appears to point that direction. The 2003 Outdoor Recreation in America report underscores a decrease in participation of outdoor recreation activities starting in 2001 and more strongly in 2003.[30] Statistics by the National Park Service show a general reduction in backcountry camping numbers since the 1990s.[31] And a 2005 Outdoor Industry Association research report suggested that the "overall popularity of outdoor activities in 2004 failed to exceed the levels measured three years [prior]."[32] Does this mean that interest in adventurous outdoor activities will continue to drop? Based on this early and rudimentary investigation, the answer is yes. Certainly, outdoor activities will still hold the interest of the Millennials, but based on generational analysis, we will see a gradual decline in interest and participation levels. The decline will be long term and will extend beyond the Millennials through the following generation. Paralleling the decline in interest will be a corresponding decrease in the number of outdoor manufacturers, guides services, outdoor schools. The programs and businesses that survive during this period will do so based on their ability to understand and adapt to the Millennials and the generation that follows them. Millennials are a generation that work well together. They enjoy the company of one another. They are different than Boomers who were more individualistically inclined and often did things in the outdoors because of philosophical reasons not unlike Thoreau's. And they are different than Gen-X'ers who did things in outdoors for the adrenaline rush. Millennials —the generation to which programmers of activities and purveyors of outdoor equipment must now adapt—will primarily engage in outdoor pursuits for recreation and the simple pleasures of being with friends. They don't need to risk life and limb nor do they need to escape like Thoreau. The Millennial Generation will have its pioneers, its risk takers, of course—all generations do—but collectively, risk in recreational pursuits will play much less of a role than it does now. Millennials will be busy, facing and overcoming challenges of everyday life, and their time for outdoor experiences will be limited. The exact form that outdoor recreation will take over the next several of decades is unclear. No one has that clear of a crystal ball. Nonetheless, what is clear, at least from the perspective of generational analysis, is that the outdoor recreation panorama will take on an entirely different form than what it is now. What about the Boomers? They started the most recent expansion of outdoor adventure activities. What is their future as they age and move into elderhood? If past Idealist generations are any guide, we will see Boomers become more realistic and farsighted. They will help guide younger men and women as they are faced with challenges and crises. The "Me" generation will evolve into "We." We'll see many of them surrender their individualism and abandon their narcissistic ways. Already we are seeing evidence of that in the outdoor literature. Maria Coffey's Where The Mountain Casts Its Shadow: The Dark Side of Extreme Adventure warns of what it's like on the home front when lives are lost on mountaineering expeditions.[33] In a departure from his previous works—and adventure literature of his generation—David Roberts in his new book On the Ridge Between Life and Death, examines his life as a mountaineer and finds it selfish and narcissistic. Although his outdoor adventures in the mountains were a source of pride and gave him great joy, he counters with two telling sentences which conclude the book: "In the human heart, however, there are nobler feelings than pride. And there are more important things in life than joy."[34] When will the next outdoor wave hit? From a generational standpoint, we won't see the next great expansion in outdoor activities until the next Idealist Generation appears on the scene. That won't occur until about the middle of this century (around 2050). Conclusion This is an early attempt to examine outdoor history through the eyes of generations. The generational cycles that Strauss and Howe have described in their work, at least from this initial investigation, appear to be applicable to outdoor adventure activities. The idea of generational types may also be helpful in guiding our understanding of how attitudes and interests will change in the coming decades. Certainly much more needs to be done, but in the interim, the use of generational analysis provides use with a new and thought-provoking tool in the study of the past, and perhaps the future. End Notes

The author expresses his appreciation to the editors for their permission to depart from APA style convention normally utilized in the outdoor education field. Instead citations in this paper are formatted according the Chicago Manual of Style, the accepted style for historical research. There are many advantages of the use of this style when it comes to citing historical works. Given the considerable number of references involved in this study, its use greatly aided the process of providing proper and fully documented attribution. [1] William Strauss and Neil Howe, Generations: The History of America's Future 1584 to 2069 (New York: William Morrow, 1991), p. 36. [2] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, vol. 2., trans. Henry Reeve (New York: Collier & Sons, 1900), p. 62. [3] Alexis de Tocqueville, L'Ancien régime (1856) in Peter Kemp, ed., The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Quotations (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), p. 104. [4] Peter Stark in his introspective book of running Mozambique's Lugenda River uses the phrase "hunger for adventure" to describe humankind's almost instinctual need to explore. I use it here, in a slightly different manner, to describe the meaning of pure adventure. Peter Stark, At the Mercy of the River: An Exploration of the Last African Wilderness. (New York: Ballantine Books, 2005), p. 175. Another term which aids in describing this limited definition of adventure is "anti-material" which was used by Peter Holger Hansen. See Hansen, "British Mountaineering, 1850-1914," p. 143 (fully cited below). [5] William H. Goetzmann, New Lands, New Men : America and the Second Great Age of Discovery (New York: Viking, 1986). [7] The Social Movements chart is based on a compilation of information from Strauss and Howe, Generations, pp. 86-90, 92-96. [8] In their later work, The Fourth Turning, Strauss and Howe use the term "archetypes" instead of generational "types." And instead of "Idealist," "Reactive," "Civic" and "Adaptive," they use "Prophet," "Nomad," "Hero," and "Artist." For the purposes of this paper, I have kept their original terminology. William Strauss and Neil Howe, The Fourth Turning: An American Prophecy (New York: Broadway Books. 1997) pp. 72-90. [10] In three of their early works, Straus and Howe refer to Generation X as the "Thirteenth Generation." In their more recent Millennials Rising published in 2000, they utilize the more common name "Generation X." [11] Neil Howe and William Straus, Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation (New York: Vintage Books, 2000). [13] I would be remiss not to note that the idea of patterns in history is not without controversy. While many have found Strauss and Howe's work to be a fascinating and provocative way of looking at history, others would adamantly disagree. Michael Lind in a New York Times book review on the Strauss and Howe's Fourth Turning wrote: "The idea that history moves in cycles tends to be viewed with suspicion by scholars. Although historians as respected as Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. and David Hackett Fischer have made cases for the existence of rhythms and waves in the stream of events, cyclical theories tend to end up in the Sargasso Sea of pseudoscience, circling endlessly (what else?). The Fourth Turning' is no exception." Michael Lind, "Generation Gaps" New York Times, 26 January, 1997 <https://www.nytimes.com/books/97/01/26/reviews/970126.26lindlt.html> (11 November, 2005).

[14] Edward Whymper, Scrambles Amongst the Alps in the Years 1860-69 (London: John Murray, 1871; reprint New York: Dover Publications, 1996), p. ii (page citation is from the reprint edition).

[16] Roderick Nash, Wilderness and the American Mind (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973), p. 8. [17] Fredrick Jackson Turner, "The Significance of the Frontier in American History" (paper presented at the meeting of the American Historical Association, Chicago, July 12, 1993) in Fredrick Jackson Turner, The Frontier in American History (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1920), pp. 1-38. [18] Anne C. Rose, "Boston Unitarianism" and "Transcendentalism as an Intellectual Movement" in Transcendentalism as a Social Movement (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981), pp. 1-37, 38-69. [19] Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nature, Addresses and Lectures, vol. 1 of The Collected Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson, ed. Robert E. Spiler (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971), pp. 3-45. [20] Henry David Thoreau, Walden, (Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1854; reprint with an introduction and chapter notes by Jeffery S. Cramer (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004). [21] The 1985 edition of the River Information Digest listed nineteen rivers in the western United States on which public use was rationed by the use of lotteries or other means: Interagency Whitewater Committee, River Information Digest, 2d Ed. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1985). [22] "Gravical" appears in a number of climbing dictionaries on the Internet. Most are unattributed, but it appears that original source for many of these is: Carl Ockier, "The Climbing Dictionary," 5 December 2000, <https://home.tiscalinet.de/ockier/climbing_dict.htm> (3 December 2005). [23] Key personalities in British mountaineering are profiled in: Peter Holger Hansen, "British Mountaineering, 1850-1914" (Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 1991.) Albert Smith (1816-1860), a member of the Transcendental Generation, created a one-man show which used music, props and a series of scenic murals to chronicle his climb of Mont Blanc (pp. 65-66). The show was highly successful and inspired many others to climb Blanc and other Alpine peaks (p. 84). Members of the Transcendental Generation were also responsible for creating the Alpine Club. One the founders was Edward Shirley Kennedy (1817-1890), a climber and author, who played a key role in the club's early organizational days (p. 108-111). [24] Showell Styles, On Top of the World: An Illustrated History of Mountain Climbing (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1967), p. 23. [25] John Muir, The Yosemite (n.p.: Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc., 1912) as reprinted in The Wilderness World of John Muir, ed. Edwin Way Teale (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1976), p. 100. [26] Tom Turiano, Teton Skiing: A History & Guide to the Teton Range (Moose, Wy.: Homstead Publishing, 1995), p. 38. [27] Susan E. B. Schwartz, Into the Unknown: The Remarkable Life of Hans Kraus (New York: iUniverse, Inc), pp. 74-75. [28] For supporting reference material, see "Sources for the 'Outdoor Generation Profile' Chart" which follows the End Notes.

[29] Howe and Straus, Millennials Rising

[30] RoperASW, Outdoor Recreation in America 2003: Recreation’s Benefits to Society Challenged by Trends, Prepared for The Recreation Roundtable (Washington, DC: RoperASW, January, 2004), p. 5, <https://www.funoutdoors.com/files/ROPER%20REPORT%202004_0.pdf> (25 December, 2005). [31] United States National Park Service, Public Use Statistics Office, "Backcountry Campers Report," <https://www2.nature.nps.gov/stats/> (25 December, 2005). [32] Outdoor Industry Foundation, "Outdoor Recreation Participation Study™ Seventh Edition, For Year 2004. Trend Analysis for the United States" ([Boulder, Co.]: Outdoor Recreation Industry Association, June, 2005), p. 24, <https://www.outdoorindustry.org/pdf/2005_Participation_Study.pdf> (25 December, 2005). [33] Maria Coffey, Where The Mountain Casts Its Shadow: The Dark Side of Extreme Adventure (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2003). [34] David Roberts, On the Ridge between Life and Death: A Climbing Life Reexamined (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005), p 382. Source Material for the "Outdoor Generations Profile" Chart Transcendental Generation (b. 1792-1821) Henry David Thoreau: Henry David Thoreau, Walden, (Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1854. Reprint with an introduction and chapter notes by Jeffery S. Cramer (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004). Gilded Generation (b. 1822-1842) Mark Twain: Several fine examples of Mark Twain's outdoor adventure writing are found in Roughing It, a series of stories of his western experiences. An excellent annotated version is: Mark Twain, Roughing It, ed. Harriet Elinor Smith and Edgar Marquess Branch (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993). For an analysis of Twain's winter survival story (found in chapter 32 of Roughing It), see Henry Nash Smith, "Transformation of a Tenderfoot" in Mark Twain: The Development of a Writer (Cambridge, Ma: The Belknap Press of Harvard University, 1962), pp. 56-59.Progressive Generation (b. 1843-1859) Theodore Roosevelt: Candice Millard, Theodore Roosevelt's Darkest Journey (New York: Doubleday, 2005). For a more general biography which covers Roosevelt's adventurous days in the Dakotas, see: Edmund Morris, The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt (New York: Ballantine Books, 1979). Missionary Generation (b. 1860-1882) Mary Kingsley: Mary Kingsley, Travels in West Africa (London: Macmillan & Co., 1897; reprint, London: Phoenix Press, 2000).Lost Generation (b. 1883-1900) George Mallory: Peter & Leni Gillman, The Wildest Dream: The Biography of George Mallory (Seattle: The Mountaineers, 2000). GI Generation (b. 1901-1924) Sir Edmund Hillary: Nothing Venture, Nothing Win (New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, Inc., 1975). Also: Sir Edmund Hillary, View from the Summit (New York: Pocket Books, 1999). Silent Generation (b. 1925-1942) Edward Abbey: James M. Cahalan, Edward Abbey: A Life (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2003). Boom Generation (b. 1943-1960) Jon Krakauer & Scott Fischer: Jon Krakauer, Into Thin Air: A Personal Account of the Mt. Everest Disaster (New York: Villard, 1997). Generation X (b. 1961-1981) Pam Houston: Pam Houston, Cowboys are My Weakness (New York: Washington Square Press, 1992).

[END]

|

One of the more fascinating and provocative new ways of looking at American history was proposed by William Strauss and Neil Howe in their ground breaking work Generations: The History of America's Future, 1584 to 2069. Strauss and Howe suggest that history is a succession of generations, and that each generation belongs to one of four types which repeat sequentially in a fixed pattern. Indeed, generational research appears to support the old proverb that history repeats itself.

One of the more fascinating and provocative new ways of looking at American history was proposed by William Strauss and Neil Howe in their ground breaking work Generations: The History of America's Future, 1584 to 2069. Strauss and Howe suggest that history is a succession of generations, and that each generation belongs to one of four types which repeat sequentially in a fixed pattern. Indeed, generational research appears to support the old proverb that history repeats itself.  mind, it was perhaps not surprising that Strauss and Howe were able to find patterns and trends which repeated themselves for over 400 years. Certainly Alexis de Tocqueville would have agreed with the concept of repetition and very likely would have admired the symmetry found in Strauss and Howe's work. "History," he once said, "is a gallery of pictures in which there are few originals and many copies."

mind, it was perhaps not surprising that Strauss and Howe were able to find patterns and trends which repeated themselves for over 400 years. Certainly Alexis de Tocqueville would have agreed with the concept of repetition and very likely would have admired the symmetry found in Strauss and Howe's work. "History," he once said, "is a gallery of pictures in which there are few originals and many copies."

Transcendental (b. 1792-1821). Idealist Type. Leaders during civil war. Rapid expansion of evangelical religion. Great interest among the literati in transcendental philosophy. Examples: Abraham Lincoln, Brigham Young, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Henry David Thoreau (pp. 195-205).

Transcendental (b. 1792-1821). Idealist Type. Leaders during civil war. Rapid expansion of evangelical religion. Great interest among the literati in transcendental philosophy. Examples: Abraham Lincoln, Brigham Young, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Henry David Thoreau (pp. 195-205).  Progressive (b. 1843-1859). Adaptive Type. Children during Civil War. Good organizers. Founded many enduring fraternal, labor, academic and professional organizations. Examples: Thomas Edison, Henry James, Theodore Roosevelt (pp. 217-232).

Progressive (b. 1843-1859). Adaptive Type. Children during Civil War. Good organizers. Founded many enduring fraternal, labor, academic and professional organizations. Examples: Thomas Edison, Henry James, Theodore Roosevelt (pp. 217-232).  Lost (b. 1883-1900). Reactive Type. Soldiers of World War I. Spawned the "Roaring Twenties" and the "Jazz Age." Morals were looser. Crime soared. Era of prohibition: bootlegging and speak easies. Examples: Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald (pp. 247-260).

Lost (b. 1883-1900). Reactive Type. Soldiers of World War I. Spawned the "Roaring Twenties" and the "Jazz Age." Morals were looser. Crime soared. Era of prohibition: bootlegging and speak easies. Examples: Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald (pp. 247-260).