Canyons and Ice: the Wilderness Travels of Dick Griffith. By Kaylene Johnson, Ember Press, Eagle River, AK. ISBN 9781467509343

.

Photos, below, copyright Dick Griffith - Used by permission

There is no doubt in my mind. Alaskan Dick Griffith is the most hardened and experienced wilderness traveler of our age. Canyons and Ice is his story.

There is no doubt in my mind. Alaskan Dick Griffith is the most hardened and experienced wilderness traveler of our age. Canyons and Ice is his story.

Have you heard of him? Probably not. Perhaps, if you live in Alaska, but outside the state, he's unknown.

That's because he's never sought out publicity. He's not a grandstander, building a fan base by blogging, Twittering, YouTubing and making sure his exploits appear in Outside and a host of other outdoor magazines. In fact, he is just the opposite. You pretty much have to pry it out of him. He has been quietly doing extraordinary trips that would leave those handsome chaps appearing on magazine covers with their ripped abs and mud-streaked faces running for the exit doors.

And Bear Grylls of Man vs Wild fame? Pshaw! He wouldn't have made it through half of one of Griffith's winter Alaskan journeys, and very likely would have turned into a whimpering wreck, begging to go home - but only, of course, when cameras had been turned off.

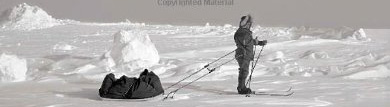

Griffith has walked and skied more than 6,000 miles across Alaska and the Canadian Arctic. Think about that. It's just under 3,000 miles across the entire U.S. from Albany, New York to San Francisco. Dick Griffith did that distance twice over - twice over! He had no roads to follow, no trails to guide his way - persevering, alone, through wild, remote country and bitter cold temperatures.

His gear? Some of the best stuff, he will tell you, came from the Salvation Army store. On some of his journeys, he didn't have maps - or what maps he had were only rudimentary.

How about GPS? It hadn't been invented yet for his early journeys. He only started using it when was 66 years old, when his legs weren't quite as strong as his younger years, and when he needed to cut back on the extra mileage that invariably crops into a long journey when using a compass and dead reckoning. But bring along a radio for an emergency? Naw, he wouldn't go that far.

The book is also about an equally tough adventurer: his wife Isabelle. It is because of her that, in 1949, Griffith was able to undertake an ambitious journey down and Green and Colorado rivers.

Griffith had met Isabelle when he was working as a guide on the San Juan River. He told her of his dream of running the Green and Colorado rivers, following the route pioneered by John Wesley Powell who led first boat party through the Grand Canyon. She had been taken by this shy but confident young man, who often only wore shorts and red bandanna tied around his head, and she offered to fund the trip with her savings. There was, however, one stipulation: she got to go.

She did go, and along with a friend of Griffith's, they launched from the town of Green River, Wyoming.

Many miles later, in southern Utah, they ran into the legendary river runner Norm Nevills. He took one look at Griffith's black, pulpous boat and told him that there was no future in rubber rafts. But Dick Griffith was not the sort of person to be swayed by someone else's opinion, even one of the most experienced boaters of that era, and he continued to use inflatable rafts - which, of course, years later would prove themselves and become the primary means of conveyance on whitewater rivers.

The summer wore on, and by the time the couple reached the Arizona border, they had to call it quits before the last segment of their journey, a run through Grand Canyon. But in 1951, Dick, Isabelle (who was now married to Griffith) and another companion were back for another go. This time they completed the Grand Canyon segment, and in the process, covered 1,200 river miles. Moreover, along the way, Griffith tackled the formidable Lava Falls solo, making the first run ever in an inflatable raft.

Their adventures together continued.

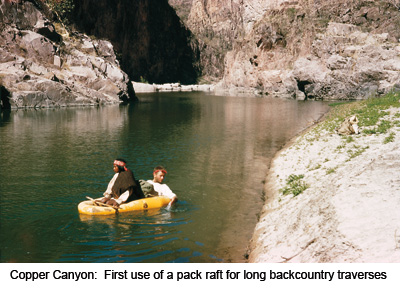

In 1952, Griffith and Isabelle and a party of three others attempted to descend Copper Canyon (in Spanish known as Barranca del Cobre) located in the Sierra Madre mountains of western Mexico. This is the home of the Tarahumara Indians known for their ability to run great distances for days at a time. The canyon's geography was largely a mystery, and all that Griffith's party had was a primitive US Air Force map.

Starting down the river in an inflatable raft, they soon came to a portage. Then another. And another. In eight exhausting days, they travelled only ten miles.

At that point, their friends had run out of vacation time and left. Griffith and Isabella soldiered on foot, abandoning the boat and other supplies to the Tarahumara. Their route took them up and over cliffs and back down to the river. At times, they needed to cross the river, and Griffith fashioned small driftwood rafts using his boot strings as lashing. Finally, out of food, he and Isabelle hiked out of the canyon and left Mexico.

They weren’t gone long. Two weeks later, they were back.

This time Griffith brought along a small Air Force inflatable raft which had been developed during the war and used by downed pilots. The raft weighed 15 pounds which meant that Dick and Isabelle could carry it along with them and use it in place of rickety driftwood rafts.

This time Griffith brought along a small Air Force inflatable raft which had been developed during the war and used by downed pilots. The raft weighed 15 pounds which meant that Dick and Isabelle could carry it along with them and use it in place of rickety driftwood rafts.

Dick was pioneering a new technique in wilderness travel - at least from a contemporary perspective. One reviewer of the book has admonished those who claim that Griffith was the first to use portable craft to cross waterways, pointing out that some native tribes of the north could transport lightweight, one person birch bark canoes over long distances.

Be that as it may, Griffith was certainly starting something new in respect to the modern age of adventure. Instead of using the term survival rafts, we now call them "pack rafts," and they are increasingly being used for wilderness travel, including ultra marathons (which, by the way, was another outdoor endeavor in which Griffith played a pioneering role).

Be that as it may, Griffith was certainly starting something new in respect to the modern age of adventure. Instead of using the term survival rafts, we now call them "pack rafts," and they are increasingly being used for wilderness travel, including ultra marathons (which, by the way, was another outdoor endeavor in which Griffith played a pioneering role).

When Griffith attempted to traverse Copper Canyon in 1952, he was a fit, 25-year-old with short-cropped, dark blond hair. In 1999, at 72 he was still amazingly fit but with a shock of white hair and creaky knees. He had lived in Alaska now for 40 some years and had travelled by his own two legs more of the Arctic than any person alive.

It was in 1999 on a winter trek in the far Canadian arctic that he was awakened one morning by the sound of heavy steps on the snow, and then a shadow moved across the tent wall. He knew immediately what it was. A polar bear.

Unpredictable, particularly when hungry, polar bears kill by stealth. Griffith carried no gun, nor bear spay. He was facing a major crisis.

He yelled and burst out of the tent, grabbing a ski, beating on his sled to try to scare it away. The huge creature with claws the length of man's foot ambled back and out of sight. Griffith relaxed a bit. Then he looked back at the tent. The long, sharp claws of the bear had torn part of the wall of the tent, missing his sleeping bag by mere four inches. He had still been asleep when it happened.

Griffith quickly prepared to leave but the bear returned to his camp. Not good. He yelled and tried scaring it off again, but this time the animal kept coming.

What happened next speaks volumes of Griffith and his life-time of experiences in the wild. I won't give it away, but believe me; you won't be disappointed with this and the rest of Dick Griffith's story of canyons and ice.

Amazon.com: More Information or Purchase