Cabin Creek Chronicle: The History of the Most Remote Ranch in America By G. Wayne Minshall

Streamside Scribe Press.

ISBN 9780984949014

Photos, below, used by permission

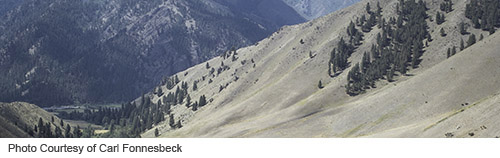

The central Idaho wilderness has left an indelible mark on author Wayne Minshall. It was plainly evident in his first historical work, a fascinating account of the Caswell brothers who through plain hard work and inventiveness eked out a living along Big Creek, a major stream in what is now known as the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness.

Minshall returns to the Big Creek country in his second book Cabin Creek Chronicles, and once again, recounts the drama of human life far away from civilization.

Even in this remote country where only a handful of people live, there are murders, adultery, and greed intermixed with a modicum neighborly goodness. His book is all focused on one piece of ground — and the succession of changes that occurred there — at the mouth of Cabin Creek, first homesteaded by the Caswells.

Minshall is the perfect person to write this account. He knows the country intimately. Moreover, he is a researcher by nature and temperament, willing to dig deeply into historical records and going to great lengths to tell the story as completely and accurately as possible.

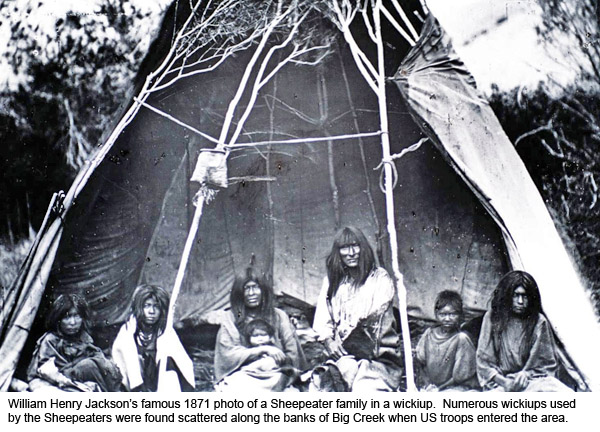

He begins the narrative before the arrival of white men with the Sheepeater Indians who had occupied the mountainous wilderness of central Idaho for millennia. A faction of the Northern Shoshoni people, it is thought that they may have found refuge from warring tribes in this land of plunging valleys and sweeping ridges.

The late Sven S. Liljeblad a prominent linguist and anthropologist described Sheapeaters as "peaceful” and held in respect by other Indians for their ability to hunt big game.

It is on the ridge to the west of Cabin Creek, and in view of the flat on which the Caswell cabins would be erected, where occurred one of the last skirmishes of the Pacific Northwest Indian wars.

The Sheepeaters had been blamed, rightly or wrongly, for the deaths of five Chinese miners. Lieutenant Henry Catley, commanding a force of 50 men, was sent to subdue and capture the Sheepeaters. On July 30, 1879, Catley awoke from his camp at the mouth of Cabin Creek. It is doubtful he slept very well and he couldn’t have been in the best of moods. He and his men were on the run.

He had been outmaneuvered by five — yes just five — Sheepeater warriors the day before, causing him to retreat. And, before evening came, he would be outmaneuvered once again by an equally small number of Sheepeaters. Minshall recounts Catley’s predicament that day and events that followed.

It was about a decade or more later that began what Minshall calls the “squatters’ period of occupation at Cabin Creek. The Homestead Act had been passed in 1862, but land could not be claimed under the act until it had been surveyed. Because of its remoteness, much of central Idaho remained unsurveyed, and therefore was ineligible to be homesteaded. Those few individuals who managed to settle on ground which might allow some semblance of farming or ranching did so as squatters hoping to one day gain official legal title.

It was about a decade or more later that began what Minshall calls the “squatters’ period of occupation at Cabin Creek. The Homestead Act had been passed in 1862, but land could not be claimed under the act until it had been surveyed. Because of its remoteness, much of central Idaho remained unsurveyed, and therefore was ineligible to be homesteaded. Those few individuals who managed to settle on ground which might allow some semblance of farming or ranching did so as squatters hoping to one day gain official legal title.

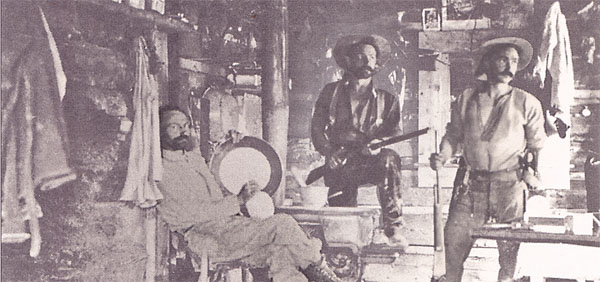

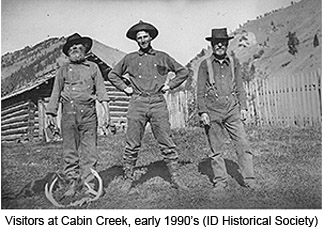

The Caswell’s weren’t actually the first squatters. When they arrived in 1894, Minshall explains, there was already a cabin at Cabin Creek, but who built it and how long they lived there remains a mystery. The Caswell’s fixed up the cabin, eventually adding other structures, along with fencing, irrigation, a newer and larger cabin, and a sizeable garden.

The Caswell Brothers. Photo Credit: Idaho Historical Society

The Caswell’s moved on and sold the squatters’ rights to another person who in turn sold them to a partnership of Mel Abel and John Routson, marking the beginning of the homestead period.

By this time the prerequisite government survey had been conducted and the land was now eligible for homestead entry. Abel made the first filing in 1911, but he made it without Routson’s knowledge.

By this time the prerequisite government survey had been conducted and the land was now eligible for homestead entry. Abel made the first filing in 1911, but he made it without Routson’s knowledge.

When Routson found out about the subterfuge, he was furious and wanted out of the partnership. Abel later described that encounter: “he wanted to sell out and walked away calling me an inbred sons of bitches and such.”

The big, muscular Routson moved off the Cabin Creek property but continued to live and work in the area. His anger festered for years and he did everything he could to make life difficult for Abel, that “inbred sons of bitches.”

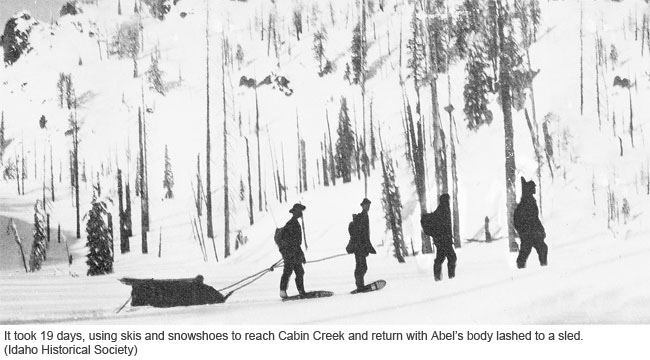

Ten years later in 1919 during a snowy December, Abel was found murdered near a haystack on the Cabin Creek where he had been feeding cattle. Four men were sent to retrieve the body. It took them 19 days, using skis and snowshoes to reach Cabin Creek and pull a sled with the body back to civilization.

Was anyone fingered for the murder? And what about big John Routson? Did he play a role? In fact, he is among the cast of characters, but I won’t divulge any more. You’ll need to read Minshall’s book to find out what transpired in this backcountry murder mystery.

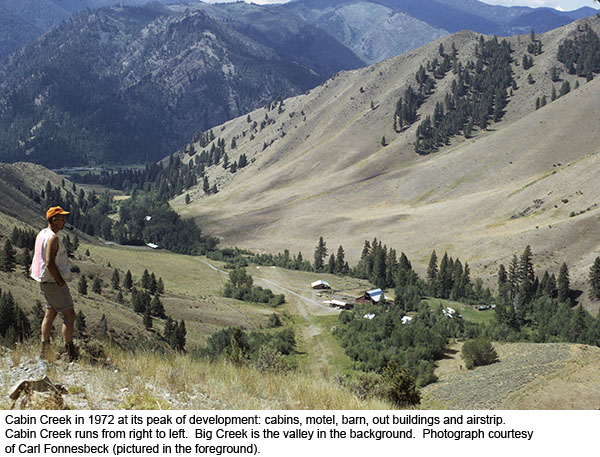

Owners, renters and hired hands came and went from Cabin Creek. After World War II as the American economy grew, the homesteads there merged and morphed into one of the first dude ranches in Idaho. Thus, began the guest ranch period.

By this time, Cabin Creek had an airstrip, and a long, multi-day horse journey to reach it was no longer necessary. New, well-heeled owners arrived on the scene with lots of capital — and a need for a tax write-off. Sportsmen could fly in, stay in ranch cabins, and be big game hunting the next day.

During the 1970’s, the movement to designate the area as congressionally protected wilderness grew. It was a process that I was integrally involved in as a board member of the River of No Return Wilderness Council, the citizen’s group working towards congressional protection.

The path to wilderness protection had actually begun well before that, in the early 1930’s with the establishment of the Idaho Primitive Area. A “Primitive Area” was a Forest Service management designation. It was an in-house regulation and could be overturned by machinations in Washington, but, nevertheless, it was an important step towards preserving the backcountry of central Idaho.

The path to wilderness protection had actually begun well before that, in the early 1930’s with the establishment of the Idaho Primitive Area. A “Primitive Area” was a Forest Service management designation. It was an in-house regulation and could be overturned by machinations in Washington, but, nevertheless, it was an important step towards preserving the backcountry of central Idaho.

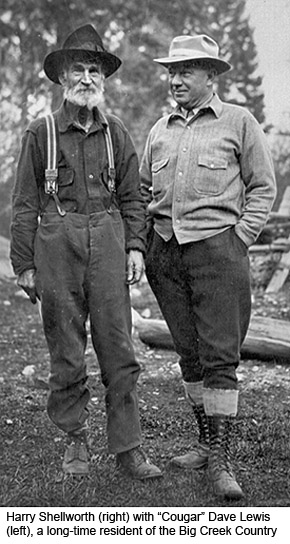

Minshall’s research turned up the name of Harry Shellworth who turned out to be a key force behind the Primitive Area designation.

Harry Shellworth was a surprise to me. In my work with the River of No Council and subsequent research about the area, I had never heard of him. But even more surprising was his background and his politics. Shellworth was a timber company executive — and he was a staunch Republican.

For an Idaho Republican and a timber executive to be a leader in preserving Idaho backcountry seems almost surreal, but, indeed, that was the case. Harry Shellworth, and those forward thinking politicians, who supported his efforts must have believed the old Greek proverb that a society grows great when old men plant trees whose shade they know they will never sit in.

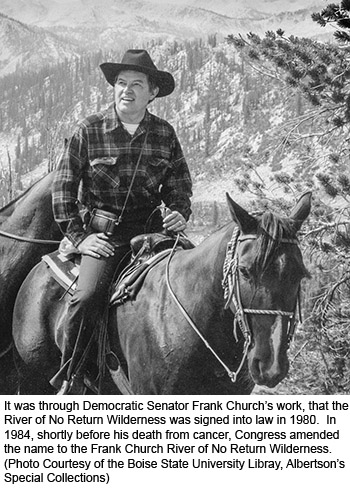

By the 1970’s, however, timber companies and Republicans were actively working against the congressional protection of the Idaho Primitive Area and adjacent roadless lands. Despite strong opposition, Democratic Senator Frank Church championed wilderness designation for the area. Minshall describes how it came about and what it meant for Cabin Creek.

His forays into Big Creek, his knowledge of husbandry, and his research background in stream ecology all come to bear in the concluding chapter of the book in which he comments on the compatible — and conflicting — values of homesteading, public land management, and historical and wilderness preservation.

Cabin Creek Chronicle is another exceptional work by a fine historical writer. Put this one on your “must read” list. You won’t be disappointed.

Amazon.com: More Information or Purchase