Introduction

In 2011, I published an article in Cross-country Ski Magazine about a 1936 ski journey into the wilderness of Idaho's South Fork of the Salmon. Undertaking the journey were Robert Gordon and Glen "Burnie" Burnside. The article that I wrote was based on two sources: a 2010 interview I conducted with Mr. Gordon and a manuscript that he had prepared of the trip. (My many thanks to Art Troutner of McCall, Idaho who first alerted me to Mr. Gordon's fastinating journey.)

Because I was limited in the amount of space available for the article, I had to leave out many parts of the story. The following is intended to rectify those ommisions.

Mr. Gordon has graciously given me permission to reproduce his manuscript in its entirely. Since the manuscript was in a type-written form, it was scanned and converted to electronic format using optical recognition software. "I don't have a computer," wrote Mr. Gordon about the manuscript. "All I have is an ancient but wonderful Underwood [typewriter] that doesn't spell well."

The Underwood spells well enough, and I have not edited his manuscript, other than correcting any errors that were of the result of the scanning process.

Here it is then, "Youth to Manhood" in Robert Gordon's own words typed on his ancient Underwood . . .

It was February, 1936. My friend Glen "Burnie" Burnside and I were playing Pinochle with his parents on a cold wintry night. Burnie, as his friends called him had graduated in 1934 from the McCall, Idaho, High School. I graduated a year after him. Burnie had worked with his dad, Bob, at the Brown Tie & Lbr. Co. sawmill. Burnie was tall, slender and tough as a Red Fir two by six.

During the course of the evening, Burnie said, "Bob, how would you like to ski into the South Fork of the Salmon river and get a mountain goat?" "Hey, Burnie, that sounds like it would be a great experience. Let's go," I responded. His mother frowned. His dad didn't say a word.

Burnie had been into the South Fork the previous year with his friend, Pete Davis, who with his dad and brother, Leon, ran several traplines in the South Fork area. Burnie said they had seen mountain goats that year, they never got close enough to shoot. The South Fork is at a lower elevation than McCall. Burnie said there was no snow when he was there last March. "You can't believe" Burnie said, "the number of deer that are grazing on the bare south hillsides where grass and other browse has survived the winter. There were hundreds of them."

Well, we planned our trip. We estimated we would be gone about two weeks. Burnie figured we ought to take about ten loaves of bread, five pounds of bacon, five pounds of oranges, we didn't want to get scurvy, three pounds of raisins, two pounds of coffee, half pound of tea, four dozen eggs, five pounds of pancake mix, five pounds of sugar, salt and pepper, matches, four candles, two flashlights. We wanted to keep the weight down, so we decided not to take any canned goods, as I recall. We had about five pounds of potatoes, two pounds of onions. We were both fond of sheepherder potatoes. That is fried potatoes with bacon and onions. Man, I start to salivate like Pavlov's dog, when I think about the tantalizing odor of sheepherder potatoes sizzling in the pan.

Well, we planned our trip. We estimated we would be gone about two weeks. Burnie figured we ought to take about ten loaves of bread, five pounds of bacon, five pounds of oranges, we didn't want to get scurvy, three pounds of raisins, two pounds of coffee, half pound of tea, four dozen eggs, five pounds of pancake mix, five pounds of sugar, salt and pepper, matches, four candles, two flashlights. We wanted to keep the weight down, so we decided not to take any canned goods, as I recall. We had about five pounds of potatoes, two pounds of onions. We were both fond of sheepherder potatoes. That is fried potatoes with bacon and onions. Man, I start to salivate like Pavlov's dog, when I think about the tantalizing odor of sheepherder potatoes sizzling in the pan.

We each had hunting knives, frying pan, small metal pots to cook coffee, tea or mix up a slum gullion of some kind. Burnie said, "we'll have plenty of venison when we get to the South Fork." I borrowed my dad's 45 caliber Smith & Weston army pistol. I was to carry the single bit ax and Burnie was going to carry his 30.06 rifle. I think it was an old First World War Springfield his grandad had given him. It weighed about eight and a half pounds plus the shells.

Burnie knew C.S. Scribner, the Supervisor of the U. S. Idaho National Forest, so he arranged to borrow two Nelson pack boards. These boards were well built with a curved canvas back and a heavy canvas sack that could be battened down.

Burnie had a good pair of store-bought hickory skis with a metal toe plate and a leather snap-throw leather binding. These bindings were the cat's meow for keeping control of your skis. I didn't have any skis so I arranged to borrow a pair of homemade skis from my friend, Bobby Kasper, his dad, Joe Kasper, was the millwright at B T & L Co. sawmill. These skis were six feet long, made out of straight grained Tamarack wood, with a leather toe strap. To hold the skis on I cut some old tire inner tubes into 3/4" bands. You put these bands on your boots and then stretched them over your toe after you had your foot in the toe strap. It worked pretty good. Your foot, of course, kind of wobbled around. As long as you were going straight it was ok. In those days we didn't know anything about fancy turns and other maneuvers. Skis were for transportation not fun.

Burnie had a good pair of store-bought hickory skis with a metal toe plate and a leather snap-throw leather binding. These bindings were the cat's meow for keeping control of your skis. I didn't have any skis so I arranged to borrow a pair of homemade skis from my friend, Bobby Kasper, his dad, Joe Kasper, was the millwright at B T & L Co. sawmill. These skis were six feet long, made out of straight grained Tamarack wood, with a leather toe strap. To hold the skis on I cut some old tire inner tubes into 3/4" bands. You put these bands on your boots and then stretched them over your toe after you had your foot in the toe strap. It worked pretty good. Your foot, of course, kind of wobbled around. As long as you were going straight it was ok. In those days we didn't know anything about fancy turns and other maneuvers. Skis were for transportation not fun.

There was a large community of Finns who lived in McCall and Long Valley. When they skied they carried an eight foot pole with a six inch wooden collar on the lower end of the pole. This pole assisted in pushing yourself uphill, kept you from slipping backwards, then you could use it to steady yourself and act as a brake going downhill. Burnie and I made ourselves two of these Finn poles out of small lodge pole pine.

We got our grub organized and proportioned where each of us had about 4# rounds apiece, plus, Burnie had his rifle and I had the ax and Distol. We planned to set out on March 15i 1936, at six in the morning. We figured the snow was considerably settled with a good crust that would make for easy going.

On the 15th it was cold and clear. It was still dark but you could see because of the whiteness of the snow. We went due East of McCall on the Lakefork Road that went by the Lakefork power plant on the road toward Slick Rock. The McCall Power & Light Co. had a small hydro generator on a small dam on Lakefork creek.

As I recall, I must tell you it is sixty one years later, that I am trying to remember this adventure. It was about nine or ten in the morning. The sun was trying to get over Jughandle Mountain. We were Cruising along, when all of a sudden, Burnie, exclaimed, "shoot, I just broke one of my leather bindings. I can't go on like this."

We had no way of fixing the broken leather strap. I had extra rubber innertube bands, but they wouldn't keep Burnie's boot in the shallow metal toemount on the ski.

Fortunately we weren't too far past the road that turned off to the power plant. Burnie says, "Hey, let me have one of your skis and I'll go to the power plant. I'll bet the operator has some tools and leather belting." We set our packs and other accouterments by the trail. Burnie took off and I sat down to wait and guard our valuable stores from any unforeseen predators.

About an hour later here comes Burnie all smiles. "Hey, I got her fixed. She's as good as new. I, also, borrowed a pair of pliers and some shingle nails." "What are you going to do-with the shingle nails!" I asked. "Oh. You never know what may come up," Burnie responded.

We had planned to make it to Slick Rock by the first day, which was about 12 miles. Burnie said there was a rough cabin there that Slick Rock Brown used as his base camp for his fall hunting parties into the Primitive Area.

We kept going. It was late afternoon. The mountain shadows began to lengthen across Lakefork canyon. We were in the vicinity of Slick Rock where the canyon walls of po1ished granite rose steeply into the sky. Burnie finally exclaimed, "the cabin should be just off the creek to the right. I can't figure this out." We kept going. No cabin. The shadows were getting longer. Finally, Burnie, emitted a loud profanity about the elusive cabin. The canyon reverberated. He could have started an avalanche. Incidentally, we learned that coming summer that Slick Bock Brown had dismantled the log cabin and moved it down into the valley.

We kept going. It was late afternoon. The mountain shadows began to lengthen across Lakefork canyon. We were in the vicinity of Slick Rock where the canyon walls of po1ished granite rose steeply into the sky. Burnie finally exclaimed, "the cabin should be just off the creek to the right. I can't figure this out." We kept going. No cabin. The shadows were getting longer. Finally, Burnie, emitted a loud profanity about the elusive cabin. The canyon reverberated. He could have started an avalanche. Incidentally, we learned that coming summer that Slick Bock Brown had dismantled the log cabin and moved it down into the valley.

Well, we decided we better find a campsite for the night, we came upon a group of Spruce trees and some dead Black pine. We got a fire going and melted snow for the coffee water. I am sure Lakefork creek was nearby, but under eight or ten feet of snow.

When I look back on this episode we were a pair of stupid jerks. We had no blankets or sleeping bags. Burnie was dressed in black wool underwear, wool shirt, wool pants and a light leather calfskin jacket. I had on regular wool underwear, wool shirt and pants, and a wool Melton jacket. I think we both wore wool stocking caps.

We spent the night around the campfire. Constantly turning to warm the side that was freezing. I don't have any idea what the temperature was, but it was a cold clear night. We drank coffee and tea all night. We broiled some strips of bacon over the fire. We made BLT sandwiches sans the lettuce and tomatoes. We had piled some spruce boughs near the fire so we could lay or sit and somewhat relax.

By the time daylight started to creep over the canyon walls we had a fire pit that was about ten feet in diameter and four feet deep. During the night we had to be careful we didn't fall asleep and roll into the fire. We kept an eye on each other to guard against this danger.

When it was light enough to see we loaded up and started up the mountain. Incidentally, in those days the U. S. Forest Service strung a single wire telephone line from their various Ranger Stations to the Lookouts on the high peaks throughout the Forests, so it made it easy to follow the trail up to Lick Creek Summit. Now they use radio.

By the middle of March the snow has settled and firmed up so you can ski on it instead of in it. Moving through the timber we were constantly crossing bowls where the snow had been shunted of the over-hanging boughs and made pronounced dips and doodles.

We had been on our way a short time with Burnie in the lead, about a hundred feet ahead of me. He was negotiating the ups and down real well, but I was struggling to keep my skis on when I tried to push myself up the slope of the bowl with my pole. I went into one of these dips when I heard and ominous crack. I fell on my face as one of my skis submerged into the snow bank.

"Hey, Burnie, hold up, I broke one of my skis." The ski had snapped in two, about twelve inches from the tip. What are we going to do? Burnie came back. We surveyed the situation. He said, you remember those shingle nails I picked up at the power house? We'll overlap the two Darts of the skis together and nail it." On a fallen log and with the ax we cobbled together the broken ski. It was about a foot shorter than the other ski, but it seemed to work ok.

Again, we got going, but I was careful about the stress I put on my brittle skis, I didn't want any more crack-ups.

About noon we reached Lick Creek Summit. It was a gorgeous day. The sun was warm and bright. We seemed to be on top of the world. From this divide, I estimated the altitude to be seven or eight thousand feet. The drainage flows west down Lakefork Creek into the Payette River, which continues on through the Emmett and Payette valleys to the Snake River. On the other slope of the divide the snow melt goes down Lick Creek into the Secesh River, then down to the Southfork of the Salmon River, which goes into the main Salmon River and -then the Salmon joins the Snake River about 15 miles up river from Lewiston, Idaho. Lewiston is the lowest point in Idaho. Later with the creating of dams and locks on the Columbia River and the Snake, ships and barges were able to navigate from Portland, Oregon to Idaho.

We started down Lick Creek. Let me tell you this is one spook-tacular canyon. It is a narrow deep canyon with perpendicular walls. The sun was hitting the upper reaches of the peaks. We were moving along pretty good riding our poles as a brake as we slipped downhill.

As the sun reached us the snow started to get sticky. I don't remember seeing Burnie fall, but on numerous occasions I'd be sliding along at a pretty good clip when I was in the shade of the trees, but when I hit an open spot in the sun, that gluey snow would grab my skis with vengeance. Being top-heavy with the pack, I couldn't keep from plunging head first into the snow. After several episodes of this face nature my face began to feel sandpapered.

We began to hear booming and rumbling through the canyon. "Burnie," I said, "that's snow and ice coming off the upper walls where the sun was having a thawing effect. We have to be careful. We could get caught in an avalanche." Hoo boy! What a way to go, I thought.

We ultimately came to a snowslide. It was about 200 yards across and probably 50 or 60 feet deep. It was strewn with rocks and trees it had brought down the mountain. It had come down with such force it covered the creek and slid part way up the opposite slope. We had difficulty crossing this war zone.

We ultimately came to a snowslide. It was about 200 yards across and probably 50 or 60 feet deep. It was strewn with rocks and trees it had brought down the mountain. It had come down with such force it covered the creek and slid part way up the opposite slope. We had difficulty crossing this war zone.

We had to cross one more snowslide before we reached Mahoney's Camp. The artillery was picking up the pace. Constant booming and rumbling as the snow and ice came loose. Mahoney's Camp was no campground at this time of year. It was a conglomeration of huge granite boulders the size of single and double size garages. We navigated through the monsters, fascinated with their size and snowcapped headgear.

We kept going. The canyon was becoming less precipitous and Lick Creek was getting bigger. It was mid-afternoon and I was getting tired. The snow was still sticky in the open spots and crusty in the shade. "Bernie, how much further do we have to go?" "shouldn't be more than three or four miles until we hit the Secesh River. The Browns had a ' cabin last year near the confluence of the Secesh and Lick Creek," Burnie informed me.

My patukas was dragging when we finally got to the Secesh. Through the trees Burnie spotted smoke. We came up to the cabin and hollered, "haloo!" Shortly a man came out. He seemed excited and glad to see us. He asked us what we were doing. We told him we came down from McCall to get out of the snow and we were headed for Clyde Parks' ranch.

The Browns, Mr. and Mrs., treated us like long lost sons. They ' seemed glad to have someone to talk to. I cannot remember their first names. They fed us bear roast, which I had never tasted before. Burnie and I, both thought it tasted a little like pork. We were hungry and it was a treat. The Browns wanted us to stay overnight, but Burnie said we wanted to get to the Clyde Parks' ranch. I was willing to stay overnight. I was "tarred", but somewhat revived by the chunk of bruin, of which we partook.

The Browns loaned us two blankets apiece and told us it was about two miles downriver to Clyde's cabin. They asked us to come back and spend the night, and we would play some pinochle. We told them we played pinochle and would be glad to come back. Burnie promised them we would bring some fresh venison if we had any luck.

We got to Parks' cabin about dark. It was a small compact one-room building, about 12' x 16', made out of logs and a shake roof. When we opened the door and walked in the pack rat stench was terrible. The floor was littered with droppings. They had crapped and urinated all over the table and the little cook stove. Fortunately there was an old broom, so we set to work dunging out the place. When we started a fire in the cook stove, that accentuated the stink. To this day I can still remember that pack rat odor. It was sickening.

I was so bushed, I curled up on the floor with two of the blankets. Burnie had strength enough to start cooking some bacon and eggs. He hollered at me, "come and get it." I moaned, "that I wasn't long for this world and didn't feel like eating." That bear was still growling in my stomach. I went to sleep and slept till noon the next day.

The snow was pretty well gone in this area. In the timber and on the north slopes of the mountains the snow was hanging on, but we could now walk. The Clyde Parks' ranch was homesteaded. I believe it was 160 acres on Zena Creek. Clyde had built a ditch from higher up on Zena Creek to bring water down to some of his flatter ground. It did not look much like a ranch. No barn. No livestock. It looked more like a park. It was covered with beautiful Ponderosa Pine trees. "Gosh!" I thought what a beautiful setting. At this time there were no roads into this country, but later during World War II they punched a road up Lakefork Creek, down Lick Creek and the Secesh to the South-fork of the Salmon. Thousands of logs went back up Lick Creek to the sawmill at McCall. I am still amazed how they built a road in Lick Greek canyon.

The snow was pretty well gone in this area. In the timber and on the north slopes of the mountains the snow was hanging on, but we could now walk. The Clyde Parks' ranch was homesteaded. I believe it was 160 acres on Zena Creek. Clyde had built a ditch from higher up on Zena Creek to bring water down to some of his flatter ground. It did not look much like a ranch. No barn. No livestock. It looked more like a park. It was covered with beautiful Ponderosa Pine trees. "Gosh!" I thought what a beautiful setting. At this time there were no roads into this country, but later during World War II they punched a road up Lakefork Creek, down Lick Creek and the Secesh to the South-fork of the Salmon. Thousands of logs went back up Lick Creek to the sawmill at McCall. I am still amazed how they built a road in Lick Greek canyon.

After Burnie and I got rested up we decided to go down the Secesh, to the Southfork of the Salmon. Maybe we would get ourselves some fresh meat. We walked down to where the Tailholt Lookout trail branched off to the left. At about this point we began seeing deer grazing on the south slopes. The further we descended along the Secesh the more deer appeared. "Burnie shoot a young so it won't be so difficult to carry." Burnie took aim, Whamo! He hit what looked like a young yearling. Incidentally, the bucks shed their horns during the winter, so in the spring you can't tell a doe from a buck at a distance. Later on this was to cause us great feelings of guilt, especially me. The yearling Burnie shot dropped down and sat there looking at us. Burnie said to me, "go up there and put him out of his misery." I had the 45 caliber pistol. I moved up towards the deer. It kept looking at me with huge mournful eyes. My conscience overwhelmed me. "Burnie,"I cried, "I can't do it." About that time the yearling jumped up and three-leggedly started down the mountain. I immediately forgot my conscience and started after him. Periodically he would stop. He didn't have those sad eyes focused on me so I took deliberate aim. Whoom! I missed. He took off again down the mountain. Several more times I tried to bring him down. Bang! Bang! No luck.

I chased the yearling down to the Secesh. There was considerable snow piled up in the river and on its banks. I tracked him till he disappeared over a large hump of snow. I crepted up. No deer. Then I saw his ears sticking up on the other side of a snow bank in the river. He was trying to hide. I sneaked up a little closer. I could now see his head. He wasn't looking at me. I took dead aim at his head and pulled the trigger. Whoom.! The deer startled began fording the river to the opposite bank and clambered up the bank about 50 feet and stopped. I had shot the last of my six slugs. The rest of my ammo was back at the cabin in my pack.

Burnie told me later, he thought is was great sport to watch me chase the deer down the mountain, wasting my bullets. Burnie finally came down to where I was watching the deer. The deer stayed on the high bank watching us. Burnie sighted him in and whamo! The deer collapsed and slid down to the river. The water was low so we had no problem getting across to where the deer lay. We cut his throat, gutted him out and split him down the middle. Each of us was able to carry a half. We cut off the head and legs to lighten the load. We kept the liver and heart. We'd have liver and onions tonight with our sheepherder potatoes. Happy day!

Back at the cabin we hung up our meat so the pack rats couldn't get to it. The next day we decided to go adventuring. We headed down the Secesh again, but this time we kept going until we hit the Southfork. This was a pretty good size river even in March. The day was beautiful and warm. Again we saw deer in the hundreds grazing on the southern hillsides. They all looked like does. We weren't after deer today, we were exploring.

Burnie knew a little about the country, the Davis boys probably told him some of the history. He said, "the old Hamilton ranch should be down the river three or four miles. Let's go down and look at it. There's the story that his wife or someone had murdered old man Hamilton and he was buried on the ranch." "Hey! Let's go look for his grave," I exclaimed.

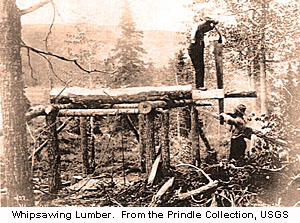

We hadn't gone down the river more than a half of a mile when we saw two guys across the river. They had a rough rectangular frame built about eight feet in the air. On this frame they had a 16 foot log. One fellow was on top with a two handled saw. The other guy was down below pulling on the other two handles of the saw. We hallooed! to them across the river. We kinda surprised them, but they answered our call. We asked, "What are you guys making?" One of them called back, "we're whipsawing some plank to make sluice boxes. Do you fellers want to help?" "No!" We answered, we didn't want to get wet crossing the river.

We hadn't gone down the river more than a half of a mile when we saw two guys across the river. They had a rough rectangular frame built about eight feet in the air. On this frame they had a 16 foot log. One fellow was on top with a two handled saw. The other guy was down below pulling on the other two handles of the saw. We hallooed! to them across the river. We kinda surprised them, but they answered our call. We asked, "What are you guys making?" One of them called back, "we're whipsawing some plank to make sluice boxes. Do you fellers want to help?" "No!" We answered, we didn't want to get wet crossing the river.

So we moseyed on down the river and finally came to the old Hamilton ranch. There wasn't much left there. We wandered around looking for Ham's grave, but never found anything that looked like a cemetery. We ate our deer heart sandwiches and decided we better head back to camp and some of those delicious sheepherder potatoes cooked with bacon. Makes me salivate, again.

The next day we decided we ought to check out the trail to Tailholt lookout. We started up the trail, but we hadn't gone very far until we ran into snow. We decided we weren't going to try to walk to the lookout on the snow. Sometimes the snow would support you and then you'd break through to your knees. No good!

My memory doesn't click in all the time. Sixty one years is a fur piece to retrace and bring up what happened. The cerebral computer is often balky. I don't think we shot another deer. We decided we would keep the two deer hams (hind quarters) to take home. We kept one front quarter for ourselves and we took one front quarter and the tenderloin to the Browns. They were pleased to see us and especially the fresh venison.

We had a delightful evening, Mrs. Brown cooked some tenderloin steaks which seemed to melt in your mouth, with potatoes and carrots. In the course of the evening they told us they once owned a newspaper in Kansas City. They were quite successful, even owned race horses. In fact on one of the walls of the cabin was displayed the hide of a horse. One of their favorite had been tanned and brought into their hideway on the Secesh. They said, they were doing well until their son got into some kind of trouble. I don't remember them relating the details. The Browns said they sold everything, lock, stock and barrel, and moved to Idaho. They built their cabin on the Secesh. All their hardware, windows, doors and other furnishings had to be packed in by horses and mules.

Their son, Slick Rock Brown, as he was known in McCall, was a packer. He had a packstring of horses and mules. I am sure he probably contract packed for the U. S. Forest Service during the summer to the , lookouts and then the numerous fires that occurred every year. I even heard stories, some of the packers start fires in order to create a little business. I never heard of anyone getting convicted for such a dastardly deed. During the fall Slick Rock took hunting parties into back country for elk, deer and bear. I don't know what happened to Slick Rock. He probably starved out, which is what happened to most of them. Packing is a seasonal business. Bad weather can very easily cook your goose in a short season. Burnie, nor I ever heard what became of the senior Browns.

After dinner, Mrs. Brown cleared the table and we got into the pinochle contest. We would change partners after each game. The Browns were good players and were gutsy bidders. They liked to win. Don't we all. It must have been around nine o'clock when we began to hear bone chilling screams outside. It put the hair up on the back of my neck. Banshees! Holy Smoke! The screams sounded like a baby in mortal pain. The Browns didn't seem to be the least perturbed. "Oh! Those are the cougars serenading us. They do it all the time. Cougars! Hoo Boy!

After dinner, Mrs. Brown cleared the table and we got into the pinochle contest. We would change partners after each game. The Browns were good players and were gutsy bidders. They liked to win. Don't we all. It must have been around nine o'clock when we began to hear bone chilling screams outside. It put the hair up on the back of my neck. Banshees! Holy Smoke! The screams sounded like a baby in mortal pain. The Browns didn't seem to be the least perturbed. "Oh! Those are the cougars serenading us. They do it all the time. Cougars! Hoo Boy!

Mr. Brown told us that Dead Shot Reed's son, Pat, came through their area every year hunting cougar. He collected a bounty from the State of $50., plus he got to keep the pelt. "Pat," he said, "had a pack of dogs. When they got on a cougar scent the dogs would go bananas, yelping and ki yi ing, they would stay after him ;or her until the cougar treed, then Pat would come up and shoot the cougar." Pat had the reputation of getting more cougar than any other trapper in the state.

During the evening Burnie and I told the Browns about ourselves. I said I had graduated from McCall High School the previous year and then went to work for Brown Tie & Lbr. Co. driving the wood slab truck. I dumped the slab wood into huge wood racked rail cars. My father, John Gordon, I further related, had an auto repair shop on the Hiway next to Dr. Hawkins' office, going south out of town. Yes, they knew of myfather. Heard he was a pretty good mechanic. This made me feel good.

Burnie told them he too had graduated from McCall the year ahead of me. His parents, Bob and Ersley Burnside lived 6n the Big Payette Lake, about a half mile west of McCall. He and his father worked at the mill. His grandfather, Tom Burnside, had homesteaded a ranch in Long Valley near Donnelly, Idaho. His aunt, Maude Howe, was the post-mistress at Donnelly. He had one brother living, Perry, who was still in high school in McCall. Donnelly is about 12 miles south of McCall.

While we were playing pinochle Mrs. Brown suggested we might want to ski over into Fitsum and visit the miners. Hey! We decided that might be an interesting adventure.

The next morning Mrs. Brown fixed one of my most memorable breakfasts. She made sourdough hot cakes with maple syrup and venison tenderloin steaks with lotsa good hot strong coffee.....yum yum.

The Browns instructed us to go up Cow Creek, which flowed into the Secesh about a mile downstream from their cabin. We were to follow Cow Creek up the mountain and when we got to the main ridge to head south down into Fitsum Creek. They said their son, Slick Rock, had built a small cabin on Fitsum Creek last fall. They had been to the cabin, but they had not been up to the mine. Bob Swanson, one of the miners had visited them last Christmas and told them their camp was about three miles up the creek from Slick Rock's cabin.

We returned the blankets and thanked the Browns for their wonderful hospitality. We found Cow Creek, crossed over the Secesh and started climbing. We got into snow again and found the going a lot tougher because of the steepness. We kept going and finally saw what we thought was the hogback ridge that separated the Secesh from the Fitsum. We ate our lunch on the ridge in bright sunshine. It was a pleasant respite. We started down into Fitsum. The snow was sticky, we sort of schussed slowly down the open hillside. Burnie was ahead of me two hundred yards. I hit a snow hump that he had crossed, but I caught a ski and went ass over teakettle. One of my skis came off and was heading down the mountain. I hollered at Burnie to catch my ski. By the time he heard me and turned around, my ski passed him. Burnie took after my ski. I got up on one ski and with the aid of the long pole I sort of one-skied down the mountain. Fortunately, Burnie found my ski. It had hit a small jackpine and turned over and stopped. If my ski hadn't hit that jackpine I could have been S. 0. S., short one ski.

We proceeded down into Fitsum. We came to the bottom. Found Fitsum Creek or what we thought was Fitsum Creek. No cabin. We didn't know which way to go, up or down. We decided to explore down the creek first. We hadn't gone more than a mile when we spotted the small cabin. It was a neat little hut. It was still mid afternoon, so we decided to find the miners. We back tracked to the spot where we first hit the Fitsum. We kept climbing. It was slow going on the sticky snow. I was getting "tarred". I hollered at Burnie, "do you think we missed their camp?" Burnie replied, "I don't think so, we'll come to it soon." A short time later, we heard three booms. About a half a mile ahead of us on the side of the mountain we could see puffs of smoke arising. On above the smoke we saw two men walking along the hillside.

Their camp was on the creek among some huge rocks, about a fourth of a mile from the mine, which was up on the side of the mountain. We hollered at the miners and they stopped and waited for us to catch up to them. The first thing they wanted to know "Do you fellows have any tobacco?" Burnie said, "No! We don't smoke." "Shit," said one of the miners. No tobac!"

The miners were glad to see us and bid us welcome to stay with them. They had plenty of food. Their camp consisted of three large tents mounted on four foot walls made out of blackpine poles and a pole frame to support the tent canvas. They had a cookhouse, where we ate and played cards. A bunkhouse with five cots and a stove. Then there was a commissary tent for supplies. In between the big rocks they had a chicken coop. I think they had ten or twelve hens. I never heard a rooster crow. Maybe he wore himself out and died. We asked what we could do to help out. "Well," Charley the oldest and probably the boss said, "we could use some more firewood and we're getting a little low on fresh meat." I should identify these fellows. Charley Curtis, the boss, was an old hardrock miner. I had heard of him around McCall. He had spent a lot of years working in mines around Warrens and Burgdorf, Idaho. I judged him to be about 65 years old. He had a grizzled beard and a face that appeared to have endured a hard life.

Bob Swanson, one of the miners, was a young man in his early twenties. He was a powerful looking specimen, built like an all-american tackle. He was clean shaven and seemed to have a perpetual smile on his face.

Blackie Wallace was a smaller man, dark hair and smoky complexion, probably how he got his name. He was the camp cook and tender. He kept up the wood supply, shoveled the snow, fed the chickens and generally kept the camp in 'ship shape.

Burnie and I, after breakfast, took their wood toboggan, saw and ax up the mountain to a stand of dead blackpine. We hauled five or six loads of wood. Blackie was pleased with our performance, because I am sure it saved him a lot of work. Blackie came out and said it was time for lunch. The miners would be down shortly. After lunch Charley asks us if we would like to go into the mine and see how an honest man makes a living. We said, "Yes, we would like to see how powder monkeys cut the mustard."

The mine shaft was probably four hundred feet into the mountain. They had a steel track of two thin rails and a small steel ore cart. Charley said, he and Bob would single jack and double jack holes into the face of the tunnel. The tunnel wasn't very large, maybe seven feet high and seven feet across. I don't remember any posts or timbering in the tunnel. I supposed Charley having a lot of experience in mines thought the character and the formation of the rock didn't pose a great danger to the miners. Sometimes it would take two or three days to get four or five holes two and a half to three feet deep. Their charge were usually two sticks of dynamite. These sticks are about an inch in diameter and eight inches long. They would prime the dynamite with a copper sheathed cap into which the fuse was crimped. The fuse was four to five feet in length. They usually set off their shots at the end of the day. That way the dust and fumes in the tunnel had a chance to settle overnight. Then the next morning they could go in and muck out, also, to see if they had exposed the Mother Lode, that would make them all rich. Bob usually did the mucking and Charley picked over the ore. He would bag the ore that appeared to have mineral in it. It looked like hard dangerous work to me. Single jacking is where one miner drills a hole by himself. He holds a short drill steel in one hand and turns it after he hits it with a three pound hammer. When the hole gets deeper they double jack it. One man holds and turns the steel and the other miner whacks it with a heavier sledgehammer.

The mine shaft was probably four hundred feet into the mountain. They had a steel track of two thin rails and a small steel ore cart. Charley said, he and Bob would single jack and double jack holes into the face of the tunnel. The tunnel wasn't very large, maybe seven feet high and seven feet across. I don't remember any posts or timbering in the tunnel. I supposed Charley having a lot of experience in mines thought the character and the formation of the rock didn't pose a great danger to the miners. Sometimes it would take two or three days to get four or five holes two and a half to three feet deep. Their charge were usually two sticks of dynamite. These sticks are about an inch in diameter and eight inches long. They would prime the dynamite with a copper sheathed cap into which the fuse was crimped. The fuse was four to five feet in length. They usually set off their shots at the end of the day. That way the dust and fumes in the tunnel had a chance to settle overnight. Then the next morning they could go in and muck out, also, to see if they had exposed the Mother Lode, that would make them all rich. Bob usually did the mucking and Charley picked over the ore. He would bag the ore that appeared to have mineral in it. It looked like hard dangerous work to me. Single jacking is where one miner drills a hole by himself. He holds a short drill steel in one hand and turns it after he hits it with a three pound hammer. When the hole gets deeper they double jack it. One man holds and turns the steel and the other miner whacks it with a heavier sledgehammer.

The rock that has no value is loaded into the steel dump cart and pushed to the outside of the tunnel and dumped. The ore in the sacks is stockpiled until summer and then packed out on mules and horses. It is then sent on to the smelter where the minerals are separated and concentrated. The miner wore a carbide lamp on his helmet. This is the way it was done in the good old days. Today they wear electric lights with battery packs. And the drilling is done with powerful pneumatic tools that can punch a hole in a fraction of the time it took by hand. I decided then and there I did not want to be a miner.

Blackie mentioned that we could use some fresh meat. Burnie and I put on our skis and took off down Fitsum toward the Southfork. About four miles down the canyon we ran out of snow. We hadn't walked very far until we began seeing deer grazing the south hillsides similar to scene on the Secesh. We kept walking towards them. They weren't spooked. They just stood there watching us. There, again, no horns. We couldn't tell the does from the bucks. Burnie pulled down on the closest one. Blam! He had a good shot. The deer dropped and lay there quivering. When we got up to the deer it appeared to be dead. When we cut the deer's throat to bleed him out, Burnie exclaimed, "sonofabitch we've shot a doe. I hope she isn't pregnant. We started to gut her out.

The guts and the transparent bag popped out. I felt sick. In this watery bag I could see two little deer. Their popeyes seemed to be quite pronounced on their little heads. I don't know how Burnie felt at that moment, but I had a terrible feeling of guilt. We had killed a mother and two babies. Sad day in Fitsum.

When we were cutting and chopping up the deer I noticed some red beads around the anus. "What are those things?" I asked. "Those are pregnant deer ticks, also, called sheep or wood ticks. They are one of numerous bloodsucking arachnids," Burnie explained. "Well, professor, how did you get so smart on ticks?" I asked. "We studied them in biology. They can cause Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever. I knew of two fellows in McCall who contracted spotted fever. They were seriously ill for a long time. Very nearly died."

If I recall correctly the two fever victims, Burnie referred to, were Reed Gillespie and Roy Nichols. Roy Nichols ran the cafe in the Lakeview Hotel. Dr. Don Numbers spent a lot time nursing them back to health. Reed is known as "Johnny Fish Planter." He backpacked a large number of fingerling trout into many of the mountain lakes in the area. He is retired in McCall and still able to spin yarns yards long.

Back to the deer ticks. As I looked closely at these ballooned ticks, I could see they were filled with little ticks squirming around in the see-through mother, probably ready to hatch.

We recovered from my guilty feeling and quartered the carcass with the ax. We had to make two trips to get all of the meat to camp. Again, we had liver, heart and onions for supper. My conscience was still bugging me. I didn't eat well.

Burnie and I were starting to get a little antsy about getting home. We thought our folks might be getting a little concerned. We told them we would be gone about two weeks. So we told the boys we were going to head for McCall on the following morning. "Boys," said Charley, "I think I'll go out with you and get some tobacco." "Fine, Charley," Burnie responded, "we'd be glad to have you break trail for us."

For two weeks the weather had been exceptionally good. On April 1, 1936, we set out at daylight. There were a few clouds blowing in from the West, but we didn't think they would amount to anything. We bid Blackie and Bob goodbye and thanked them for treating us so royally. Blackie had made us two huge venison steak sandwiches apiece. We had been on the trek about an hour when small flakes of snow began to fall.

We kept going up the canyon. The snow began coming down in larger flakes. Visibility blurred. We kept going. The snow was getting heavier and thicker. Burnie thought it wasn't too far to the summit. , "Once we get to the summit," he commented, "it would be all downhill." I like downhill better than uphill. We kept going. No summit. When we thought it was noon we stopped and ate one of our sandwiches. No coffee. T. S. After lunch we started again. By this time snow covered our skis. Poor Charley on snow shoes was having a hard time plodding through ten inches of goose feathers. We kept going. No sumit. Mid-afternoon we decided we were lost. We had no idea where we were. We knew we were supposed to be in Fitsum, but in the blizzard we had no idea what part.

"Boys," Charley counseled, "I think we better find a clump of spruce and make camp for the night. We can hit her again tomorrow, it will probably stop snowing and we can see where we are."

We backtracked down into what appeared to be the bottom. The trees were thicker and larger. We found a group of spruce and some dead black pine for firewood. We got the fire going. We chopped a large supply of wood-and some spruce boughs to sit on and stuck a number of them in the snow to kinda shelter us from the snow that was blowing through the trees. We made coffee and tea water from the snow and ate our other venison sandwich Blackie had made for us that morning

On the tree limbs, especially the spruce, a moss grows long and stringy. This moss dies and turns black, we call it "witches' hair." This moss when it is dry makes an excellent punk for starting a fire. You gather copious quantities and form it into a compact ball, put some smaller twigs on top and around it, one match and you've got a good little fire going. This witches' hair, also, makes a good toilet tissue if you don't happen to have a roll of 'Real Silk' handy. It has the smoothness of steel wool, but it gets the job done. In a forest fire I have seen dead spruce trees covered with witches' hair. When the fire reaches these trees it flares into the sky like a roman candle, a geyser of fire. At night it is a spectacular sight.

All night it continued to snow. I can't remember too much about how Charley was dressed, but I can still see Burnie turning his back to the fire. His calfskin jacket was wet and the steam was rising off of it. Charley told us stories of his earlier life. He said he'd hit a couple of good licks in his gold mining ventures, but like a dam fool he'd come to town get likkered up and blow his wad on gambling and the girls.

All night it continued to snow. I can't remember too much about how Charley was dressed, but I can still see Burnie turning his back to the fire. His calfskin jacket was wet and the steam was rising off of it. Charley told us stories of his earlier life. He said he'd hit a couple of good licks in his gold mining ventures, but like a dam fool he'd come to town get likkered up and blow his wad on gambling and the girls.

Burnie and I each had two deer hams in our packs, so we cut strips off and broiled then over the fire. With salt and pepper they were tasty. All night we broiled venison and drank coffee or tea.

When morning came. At least we thought it was morning. It was lighter. The snow was still coming down. It was a beautiful winter wonderland. Made you feel like singing "White Christmas." But it wasn't very pleasant to be bushed and know you were lost in a blizzard.

Burnie says, "I think I know what happened. Fitsum has two canyons and we went up the wrong one. We've got to bear to the south." We started out again, still snowing and blowing. I could hardly see Burnie ten feet ahead of me. The snow was getting deeper and harder to plow through. I felt sorry for poor old Charley plodding along behind us. He should have been in a nice warm retirement home, instead of stressing himself in a snowstorm. We kept going. No indication whatsoever of where we were. I was getting tired and hungry. I am sure they were too "Burnie," I hollered, "why don't we stop and broil up some venison and make coffee?" Burnie said, "lets go for a while more, maybe we'll hit the summit." We plowed on for another hour. We came to a flat spot. It stayed flat. We kept going, still flat. I looked up through the swirling snow and momentarily I saw a huge rock formation looming above us. I hollered at Burnie, "what the hell is that?" I pointed up ahead.

Burnie says, "I think I know what happened. Fitsum has two canyons and we went up the wrong one. We've got to bear to the south." We started out again, still snowing and blowing. I could hardly see Burnie ten feet ahead of me. The snow was getting deeper and harder to plow through. I felt sorry for poor old Charley plodding along behind us. He should have been in a nice warm retirement home, instead of stressing himself in a snowstorm. We kept going. No indication whatsoever of where we were. I was getting tired and hungry. I am sure they were too "Burnie," I hollered, "why don't we stop and broil up some venison and make coffee?" Burnie said, "lets go for a while more, maybe we'll hit the summit." We plowed on for another hour. We came to a flat spot. It stayed flat. We kept going, still flat. I looked up through the swirling snow and momentarily I saw a huge rock formation looming above us. I hollered at Burnie, "what the hell is that?" I pointed up ahead.

Burnie peered through the snowy mist until he saw the rock mountain. "Hey! I think I know where we are. We are on North Fitsum Lake and that mountain is the back of Old Nic ." "We evidently," Burnie explained, "missed the main Fitsum canyon and came up the North Fitsum. We've got to go back down to the main canyon."

It is still snowing, fortunately., it isn't too cold. We made an about face and started back down the North Fitsum. We could not see our tracks. We knew we had to go down hill. We kept going down. Burnie in the lead breaking trail with Charley mushing along in the rear.

We finally got back to what we thought was the main canyon. The light seemed to be waning as the snow continued. "Boys!" Charley admonished us, "we'd better find a place to make camp. We can't make it over the hump this late in the day." Burnie and I concurred with Charley's counsel.

We kept going down hill. Luckily we came to our clump of spruce where we had spent the previous night. Burnie and I chopped some wood and got a roaring fire going in the pit we had melted the night before. Again, we spent a miserable night sitting around the fire, alternately turning to warm ourselves. All night we broiled strips of venison and drank coffee or tea. During the night I watched Charley whittling on a piece of green spruce bough. "What are making, Charley, a talisman to bring us luck and get us out of this mess?" "No! I am carving a plug for my bunghole. The cheeks of my ass are chafing together and it's sore as hell. I'll stick this plug up my ass and it'll keep the cheeks apart." "Boy!" I said, " I never heard that one before. Must be Indian medicine." "No. an old trapper taught me that trick. He could have picked it up from the Indians, I don't know."

During the night we got to talking about our situation. It looked pretty bleak. Charley suggested, "maybe we better leave a note in case we don't we make it. I've got an old Prince Albert tobacca can. One of you boys got any paper?" Burnie said, he had a little notebook. He wrote a brief message, mentioning our names and that we were going to try to make it back to the mining camp on Fitsum. We made a two foot long blaze mark on the biggest spruce and Burnie used one of his precious shingle nails to nail the can on the blaze mark. Nobody ever reported finding our message. It could probably be still there.

The next morning the snow started to taper off. We had a fire hole about eight feet deep. We had built the fire over the creek, we could see the water running in the bottom of the hole. Too bad we had to leave, we had running water in our kitchen.

All three of us were bushed. Forty eight hours with hardly any sleep. We decided we better go back to camp. It was approximately 25 miles to McCall, probably five miles up hill to Fitsum summit.

We wallowed our way back to camp. Blackie seemed surprised and tickled to see us. He said, "Bob and I were concerned about you guys because it started snowing shortly after you took off." Blackie fixed us a good lunch, then we tumbled into our sacks and conked out. We slept till noon the next day.

On April 5th it was clear and cold so we decided to make another stab at getting home. The new snow made it tough going but we got to the summit about noon. What a beautiful sight. We could see Brundage Mountain glistening in the distance. It was a long ways away. It comes back to me, faintly, that there was an elevation sign just above the snow line that read 8,700 feet. I judged we were about a mile south of old Nic , which is the highest point. The Forest Service map shows it to be 9,100 feet above sea level.

We ate Blackies sandwiches in the bright noonday sunshine. Pleasant. We surveyed our situation. The terrain that sloped west off the mountain was steep and wide open. No trees. Off to the right a large number of trees were interspersed all the way down to the bottom. "Boys," Charley suggested, "we better go down through the trees. It will be safer." Burnie and I were intrigued with the gorgeous ski run off the mountain. It looked like a two-mile Joy ride. After we finished eating, Burnie said, "I am going to ski that hummer." "Burnie, that is dangerous, with the new snow, you could start an avalanche very easily," warned Charley. "I'm going," said Burnie as he put on his skis and hoisted his pack on his back. "I'll meet you guys at the; ranger station. Maybe I'll have dinner cooking for you." Burnie wasn't going to schuss the incline. He angled diagonally across the face of the mountain. We watched, intently, as he descended rapidly riding his pole to the side. We thought we heard cracking sounds as he speedily traversed the open slope. We concentrated on his descent as he smoothly made his way down the mountain. Nothing happened. We both breathed a sigh of relief when Burnie reached the bottom. He stopped, turned and waved to us. Well done, Burnie.

"Charley, I am going to follow Burnie's tracks. I'll wait for you at the bottom. Ok?" "Well, Bob, it's your decision. I think it's foolish. You heard the cracks as Burnie went down. It's a mighty dangerous situation. You could get killed very easily," Charley argued in my behalf.

I started down. Immediately I could hear the cracking sounds and it felt like the snow was settling under me. This raised the hair on the back of my neck. I was scared. I should have listened to Charley. I kept myself in a low crouch to keep my balance, going as fast as I could. Riding my ski pole to keep my balance, yet I didn't want to slow myself too much. Periodically as I went down I could hear the snow crack and could feel the settling action. Man! was I glad to get to the bottom. My legs were quivering from the strain, both mentally and physically. I waved back up the mountain. I could see Charley, occasionally, as he descended down through the trees. It took Charley about three quarters of an hour to snowshoe to where I was sitting on my pack.

We followed Burnie's tracks for a couple of hours when up ahead I could see smoke arising from the Lakefork Ranger Station. "Hey, Charley," I Hollered, "Burnie's got supper agoing." When we got up to the entrance gate of the compound, we were puzzled. Burnie's tracks did not turn in, they went straight down the road towards McCall.

Charley and I surmised that some Rangers were at the station and Burnie didn't want to chance getting caught with the deer hams. I said to Charley, "I'm pooped, I can't make it to McCall tonight. Let's see if we can stay the night with these guys." We made our way to the ranger station. We saw two sets of skis in the snow. We saw their the tracks where they had climbed up a shed type roof on one end of the main building and entered through an upstairs window.

We hallooed, pretty soon a fellow stack his head out of the window. We asked if we could stay overnight with them. "Sure, Come up!" We climbed in. I was apprehensive about my pack and it's one and a half, deer hams. I put it in a corner of the room. No questions. Charley and I introduced ourselves and found the two rangers from McCall were Bill Fritchman and Gene Powers, who both Charley and I knew. Bill in addition to being a ranger was, also, on the school board. They had plenty of food so Charley and I partook of their spam and beans. The rangers had come up to the station to measure the snow and the water content. They gave us two kapok sleeping bags apiece. We told them of the mine over in Fitsum and our experience of being lost in the blizzard for two days. They said we were lucky to get out of that jackpot. We agreed with them.

The next morning after a hearty breakfast we closed up the station. Bill and Gene had already shoveled off the roofs of the buildings. We trekked our way towards McCall. The rangers had driven their pickup to the Blackwell ranch where the County stopped plowing the road. When we got into McCall they let Charley off at the Brundage Hotel. I thanked Charley for all he had done for Burnie and me.

I told the rangers I'd ride with them to Headquarters as I lived a quarter of a mile from there. I thanked them for their hospitality and the ride. I never knew when Charley went back to the mine. I don't know if Blackie ever got his "tobac."

I saw Burnie that afternoon at his house. He had just gotten up. I ask why he didn't stop at the ranger station. "Hell! he said, "I wasn't going to check in with those 'Federales,' with me having those deer hams in my pack." I ask him what time he got home. He said, "about 8 o'clock. I was bushed about like you were that first night at Park's ranch. I was too 'tarred' to eat, I just flopped into bed."

So ends the narrative of a boy crossing the vague line into manhood. One of the best lessons a young feller can learn is self reliance. This three-week excursion was a good one in this regard. If I might add this personal observation I have made of kids that have been raised on a farm. These kids learn how to work and they develop a strong self-reliance, because on a farm there are always problems that have to be taken care of by someone. These qualities are some of the finest gifts parents can give to their children.

EPILOGUE or POSTLOGUE

Glen "Burnie" Burnside was married in 1936 to Hulda Maki, a farm gal and school teacher from down the valley. They had one son, Denny. Burnie continued working for B T & L Co. for a number of years. Later he and Hulda moved to Salem, Oregon, where he became a successful building contractor. The last time we saw Burnie and Hulda was at a School Reunion in McCall in 1991.

Bob Cordon continued working at the mill until it burned in the summer of 1940. I moved to Boise in Dec. 1940. After a short stint in the Army, completed a business college course and went into insurance and real estate. I was married to Ione Johnson, a McCall girl, in 1946. We have one daughter, Gretchen. We live in East Boise on a rocky knoll surrounded by spruce, white fir, junipers and mountain ash. We tried to bring some of the mountain ambiance to our homestead.

END

A Great Read...

If you enjoyed this story, you would also enjoy Never Turn Back. It's been widely acclaimed by reviewers and readers alike. The standard book trade reference Books in Print calls it a "masterfully written book" and "one the outdoor world's finest works." The book also appears on a number of best reading lists. Click here for more information. |

||||

And Another . . .

The book is truly a classic, one reviewer calling it the "standard by which other guidebooks are judged." Click here for more information on Winter Tales and Trails.

|

||||

More Resources...

|

||||

If you are interested in more stories of skiing in the old days, you'll want to pick up a copy of Winter Tales and Trails. It's full of historic information on skiing. Plus, it's a guidebook to backcountry, cross-country and snowshoeing trails in Idaho, Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks.

If you are interested in more stories of skiing in the old days, you'll want to pick up a copy of Winter Tales and Trails. It's full of historic information on skiing. Plus, it's a guidebook to backcountry, cross-country and snowshoeing trails in Idaho, Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks.