Defending Idaho's Natural Heritage

By Ken Robison.

Boise, ID.

ISBN 9870578140933

Defending Idaho's Natural Heritage is an impressive and penetrating history of Idaho's conservation movement, and there was no better person to write that history than Ken Robison.

Ken Robison is a journalist and for many years served as the editorial editor at Idaho's flagship newspaper, the Idaho Statesman. He was later elected to the Idaho legislature, but he continued reporting and writing on environmental issues, founding a magazine called the Idaho Citizen.

He was present on the scene, a keen-eyed observer and reporter, during the most tumultuous — and productive — times in the Idaho conservation movement.

It was during the three decades of the 1960’s, 70’s and 80’s that monumental battles were waged over Idaho’s wild lands and rivers. These were David and Goliath battles: small Idaho-based conservation groups and individuals with little or no funds up against business lobbyists and corporate lawyers with unlimited expense accounts.

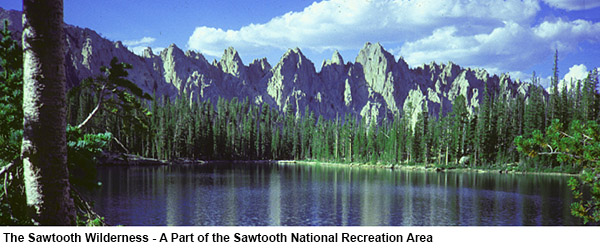

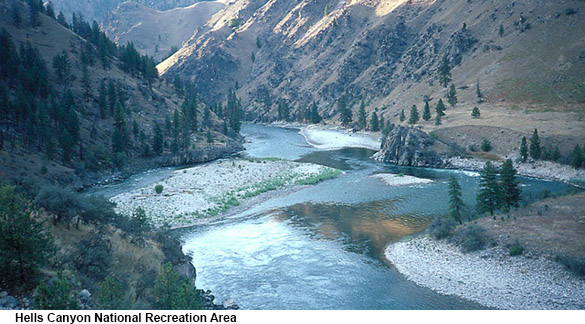

What came from those struggles are such national treasures as the River of No Return Wilderness, the Sawtooth Recreation Area, the Selway-Bitterrroot Wilderness, and Hell’s Canyon National Recreation Area.

Robison delves into the issues involving each of these areas and rivers, highlighting the individuals involved, and tracing the political ups and downs.

Idaho environment groups had help from national organizations, but much of the work of protecting these areas was undertaken by Idahoans. Considering that Idaho is one of the most conservative states in the nation, it was no easy task.

By the middle of the last century, most of the contiguous United States had been developed, but Idaho was one of those fortunate states to still have wild lands and rivers. The state had been shielded from the harried growth that occurred elsewhere by virtue of its geography. Rugged mountains and plunging valleys left large areas relatively untouched.

But not long after World War II, things began to heat up in Idaho. The Depression years were fading in memory, and the nation’s economic engine brought back to life by war spending, was barreling along with no slow-down in sight. There was money to be made, particularly in the heretofore untouched mountains of Idaho.

Timber previously considered uneconomical was now in demand and logging roads proliferated on Idaho forest lands. Mining companies were staking more and more claims. Some exploration methods involved bulldozing up and down mountainsides. Mineralized stream beds were being dredged leaving a wasteland of gravel piles.

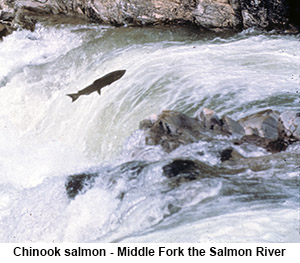

Pushed by agricultural and power interests, the federal government was on a dam building frenzy, and potential dam sites were being located on such pristine rivers as the North Fork of the Clearwater and the Middle and Main Forks of the Salmon. Those and other Idaho rivers were clearly in the crosshairs.

Pushed by agricultural and power interests, the federal government was on a dam building frenzy, and potential dam sites were being located on such pristine rivers as the North Fork of the Clearwater and the Middle and Main Forks of the Salmon. Those and other Idaho rivers were clearly in the crosshairs.

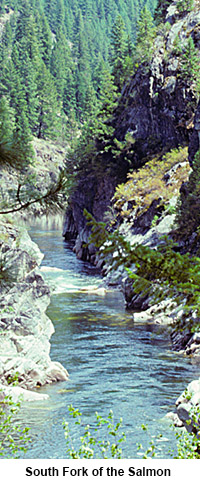

In the 1950's and 1960’s, the environmental damage from increased development and resource extraction was becoming obvious. A network of logging roads to the east of McCall washed away in the spring melt-off of 1965, sending tons of debris into the South Fork of the Salmon, the single most important Salmon spawning stream in the Columbia basin.

Key salmon spawning beds were covered with as much as 18 feet of silt. The salmon fry hatching from eggs were doomed, of course, suffocating and dying in great numbers.

Under pressure from logging companies, the Forest Service was spraying hundreds of gallons of DDT on trees to kill invasive insects. But that’s not all that DDT was killing. It was later determined to be so toxic to the environment that it was later banned.

Toxic chemicals from mining tailings were leaking into water courses, poisoning fish and other aquatic life in such streams as Panther Creek, a tributary of the Salmon River. And more and more roads were penetrating once wild areas.

It was the sportsmen of Idaho — hunters and fisherman — who first sounded the alarm loud enough to be heard by politicians, and it was sportsmen organizations, primarily the Idaho Wildlife Federation, that began the early attempts to try protect wildlife habitat. But they quickly found themselves against well-funded foes: timber, mining and power companies, the farm bureau, and politicians, then as they are now, heavily influenced and funded by business and wealthy backers.

It was the sportsmen of Idaho — hunters and fisherman — who first sounded the alarm loud enough to be heard by politicians, and it was sportsmen organizations, primarily the Idaho Wildlife Federation, that began the early attempts to try protect wildlife habitat. But they quickly found themselves against well-funded foes: timber, mining and power companies, the farm bureau, and politicians, then as they are now, heavily influenced and funded by business and wealthy backers.

What makes Defending Idaho’s Natural Heritage such a valuable work is its accuracy. Robison, from his many years as a journalist, is a stickler for getting the facts right. The research for the book, itself, took five years, and he has carefully documented the work with 30 pages of source notes.

Robison takes an impartial approach in the book, but between the lines, we are reminded that our outdoor heritage is not a given. It’s not an accident that we have wild lands, free-flowing rivers and protections from those who would damage the outdoor environment. It’s there because of the hard work and sacrifices of men and women in past – and in the present.

Nor can we take past successes for granted, for there are politicians in Idaho and other states’ legislatures and members of the US Congress who, at the urging of moneyed interests, are exploring ways to dismantle the nation’s system of land preservation. That's why Ken Robison's book is important now - and will be important in the future. If we don't learn from the mistakes of history, to paraphrase the famous quote, we are doomed to repeat them.

Robison’s book is one of the most important works on the Idaho conservation movement ever to be published, and it will long be a reliable source of historical information.

Defending Idaho can be purchased directly with the author's site: Defending Idaho