The Last Voyageur: Amos Burg and the Rivers of the West by Vince Welch

The Last Voyageur: Amos Burg and the Rivers of the West by Vince Welch

The Mountaineers Books, Seattle.

ISBN 9781594857010

Unless otherwise indicated, photos, below, courtesy of the Oregon Historical Society

This labor-of-love book is a vivid portrait of a pioneering river explorer and a welcomed addition to outdoor literature.

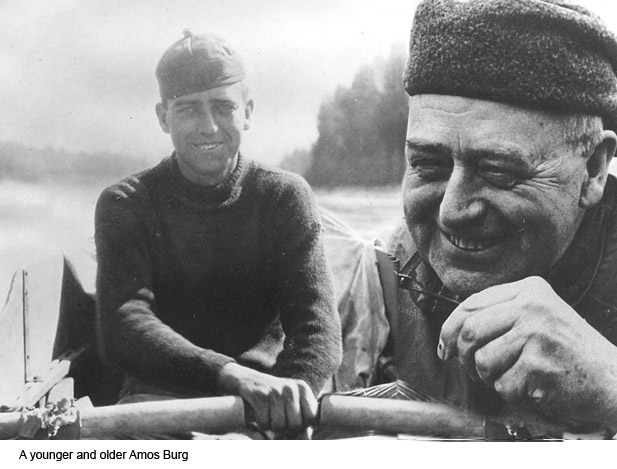

It’s about Amos Burg to whom I was first introduced many years ago through a photograph. It was actually two photographs and both captured my imagination.

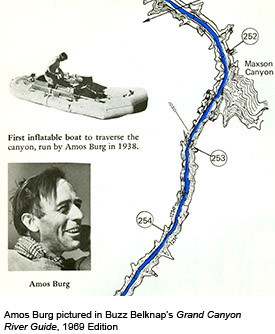

The photos were in a Grand Canyon guidebook, shown below, that I was using to navigate the river in 1974. One photo showed a rubber raft topped with wooden frame and a man standing in it, stooped over, packing something away. Just below was a close-up of the man. The caption read: “First inflatable boat to traverse the canyon, run by Amos Burg in 1938.”

I knew that inflatable rafts were being used on the Colorado River sometime after World War II but Burg was pioneering their use a full decade or two before they became common. How did he get the idea? And where did the boat come from?

I knew that inflatable rafts were being used on the Colorado River sometime after World War II but Burg was pioneering their use a full decade or two before they became common. How did he get the idea? And where did the boat come from?

Amos Burg. His name and those

questions — and that image of him in profile with hair swept to the side and a generous, broad smile stuck with me. On subsequent runs of the canyon, I would re-look at the photos and would again wonder about him.

I wasn’t the only one. Author Vince Welch writes that the two same photos had also caught his eye on trips down the river when he worked as a guide. Initially, however, he was more taken by Buzz Holmstrom, also pictured in the same guidebook, and the consummate oarsman and first to run the Grand Canyon alone.

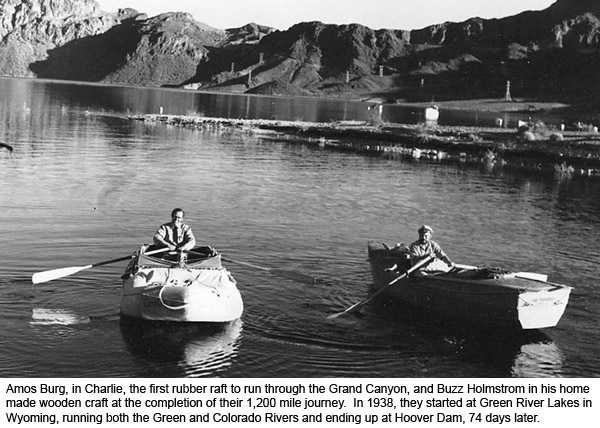

In 1937, Holmstrom launched a home-made wooden boat that he had built for $35 in the town Green River, Wyoming. He traveled over 1,000 miles, finishing the journey by rowing across the interminable Lake Meade and bumping his craft onto the concrete face of Hoover Dam.

Welch co-authored The Doing of the Thing, an outstanding biography about Holmstrom which won the National Outdoor Book Award in 1998.

After a long period of research, he is back with a new book, this time about Amos Burg. Entitled The Last Voyager, the book fills in the blanks and has greatly expanded our knowledge of the man. Amos Burg, it turns out, was an adventurer extraordinaire.

After a long period of research, he is back with a new book, this time about Amos Burg. Entitled The Last Voyager, the book fills in the blanks and has greatly expanded our knowledge of the man. Amos Burg, it turns out, was an adventurer extraordinaire.

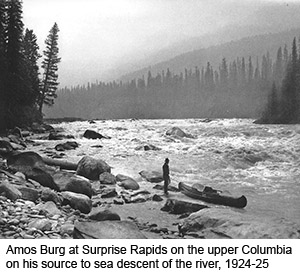

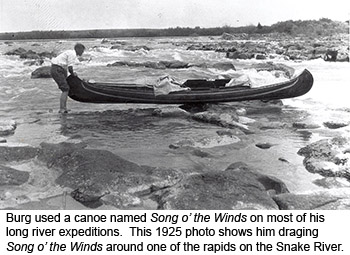

Not only did Burg run the Grand Canyon, but he also made runs of each of the great rivers of the West prior to dams. In a burst of activity over a 20-year period from 1920 to 1940, he ran the Columbia, Snake, Yukon, Mackenzie, Yellowstone, Missouri, and Mississippi Rivers. Gone for months at a time, he was both consumed and seduced by rivers and never married until very late in life.

He had hoped to be able to earn enough to make a living by writing and photographing his experiences, but it was a long shot. At end of the 1920’s, the country was slipping inexorably into a prolonged economic depression. Moreover, there were no outdoor equipment companies like today that provided paid sponsorships.

He had hoped to be able to earn enough to make a living by writing and photographing his experiences, but it was a long shot. At end of the 1920’s, the country was slipping inexorably into a prolonged economic depression. Moreover, there were no outdoor equipment companies like today that provided paid sponsorships.

If he was to be successful in being a professional adventurer, he would have to do it on a shoestring, scrimping and saving, making it from article to article — and from lecture to lecture. Initially, he borrowed funds from his father to finance his trips. Hard working and principled, Burg worried about how he would pay him back, but eventually he scraped enough money to settle up and he was relieved.

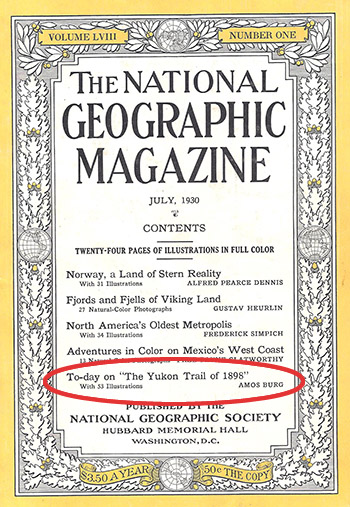

It was after running the Yukon River in 1928 when his big break came. He managed to interest the editors at National Geographic in a story of the journey, and in July of 1930, his article appeared. “His first National Geographic article,” wrote Welch, “ran forty-one pages with fifty-three photographs. He received a check for five hundred dollars (approximately $6,400 today), a substantial sum.”

It was after running the Yukon River in 1928 when his big break came. He managed to interest the editors at National Geographic in a story of the journey, and in July of 1930, his article appeared. “His first National Geographic article,” wrote Welch, “ran forty-one pages with fifty-three photographs. He received a check for five hundred dollars (approximately $6,400 today), a substantial sum.”

His next adventure was a canoe journey down the Mackenzie River in Canada and once again he sold National Geographic on the idea. By now, he had learned how to shoot movies and he hoped that by selling rights to the films and using them for his lectures, he could tap into another source of funds to keep him going.

His persistence and hard work paid off. Shortly thereafter he became a member of the Explorer’s Club in New York which greatly increased his network of contacts, leading to more lectures and article opportunities. In all, during his lifetime, he authored and photographed an impressive nine articles for National Geographic and contributed photographs for three others.

In 1938, he teamed up with Buzz Holmstrom and together they ran 1,200 miles down the Green and Colorado Rivers. Burg was in a rubber raft and Holmstrom was in a wooden boat. Burg’s decision to use a rubber raft — and subsequently proving its worth on whitewater rivers — is an important part of river history.

Welch describes Burg as “making an imaginative leap,” detailing how his interest in a rubber raft came about and how Burg obtained the craft. I could recount some of that here, but you’ll want to pick up a copy of the book for Welch tells the story well.

Burg made a film of the Green and Colorado trip, entitled “Conquering the Colorado.” When it was shown to an audience of 3,000 at constitution Hall in Washington, it was an instant hit. “Months later,” writes Welch, “the ten-minute film showed in movie theaters around the country and around the world.” It went on to be nominated for best documentary for the 1939 Academy Awards.

Welch also includes a few of his own stories that parallel Burg’s life. Along with the story of Burg’s source-to-sea run of the Columbia, there’s a short vignette of Welch’s own pioneer family first arriving in Oregon in 1844 after navigating a portion of the same river. Along with the chapter of Burg’s trip down the Colorado River, Welch includes an impressionist piece of what it’s like to run the granddaddy of rapids in the Grand Canyon, Lava Falls.

There are only a few of these diversions, but they fit and flow nicely with the book. It’s undeniable that during the process of writing, the author and the subject of a biography become inextricably linked, and incorporating some personal commentary can enliven a book — which it has done here.

Amos Burg was determined and ambitious, but he was also refreshingly modest. “Burg would have been embarrassed to find himself hoisted on a pedestal,” Welch writes. “Nevertheless, he serves as a marker on the river of time, a witness to change who wore his heart on his sleeve when it came to rivers. He traveled the western waterways in pursuit of beauty, adventure and excitement . . . . His explorations were as much of the landscape as the human heart.”

Bravo to Welch for putting an equal amount of heart into this fine biography and giving us front row seat into Amos Burg’s fascinating life.

Amazon.com: More Information or Purchase